What Really Happens To Your Body When You Have Fatty Liver Disease

According to the Cleveland Clinic, fatty liver disease is a common form of liver disease characterized by the abnormal accumulation of fat in the liver (5% to 10% of the liver's weight). The two major types of the disease are alcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Alcoholic fatty liver disease is caused by heavy drinking, reports MedlinePlus. When you drink more alcohol than the liver can process and detoxify, harmful byproducts formed in the process can inflame and damage liver cells, undermining the body's disease resistance. Similarly, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is also marked by the buildup of fat in the liver, inflammation, and liver damage; however, it is not associated with heavy alcohol use. While the cause of NAFLD is unknown, several factors (e.g., obesity and diabetes) can raise your risk of getting the disease.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can progress through four stages, as described in a review of studies published in a 2014 edition of the British Medical Journal. In the first stage, referred to as simple fatty liver (or hepatic steatosis), fat begins to build up in the liver, but there are usually no symptoms, and it is reversible. The next stage, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), features liver inflammation and carries a high risk of progression to advanced liver disease. These two initial stages, as well as the advanced stages of fibrosis and cirrhosis, similarly occur in alcoholic liver disease (via Medical News Today).

Prevalence of fatty liver disease

Affecting one in four people worldwide, NAFLD has emerged as a significant public health burden for people of all ages, per a 2020 epidemiological review published in Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology. The prevalence of NAFLD globally ranges from 13% in Africa to approximately 30% in the Middle East and South America. NAFLD is the most common cause of liver disease in Western countries, affecting an eye-opening 64 million and 52 million people in the U.S. and Europe, respectively.

Among heavy drinkers, 90% have simple fatty liver (or steatosis). Though benign, simple fatty liver progresses to the inflammatory stage (steatohepatitis) at a rate of around 35% and advances to end-stage cirrhosis at a 10% clip. Even at the middle stage of alcoholic steatohepatitis, the risk of dying by six months is 40%-50%. Alarmingly, your risk of dying increases by a factor approaching seven if you have advanced fatty liver disease (via Johns Hopkins Healthcare).

Per the 2020 review, both NAFLD and alcohol-induced liver disease are expressly linked to Westernized lifestyles. In fact, Asia and Pacific countries are seeing a greater increase in NAFLD prevalence due to dramatic lifestyle changes that mimic Western patterns. Whereas the Western model of overconsumption of calorie-rich foods along with sedentary living increases the rate of NAFLD, the combined effects of drinking at a younger age, more drinking among women, and an overall upward trend in alcohol use increases the prevalence of alcoholic fatty Iiver disease across the world.

Symptoms of fatty liver disease

Fatty liver disease, whether NAFLD or alcohol-induced, is often regarded as a silent disease, reports Medical News Today. People with fatty liver disease typically have few symptoms or none at all. Nevertheless, if the liver becomes enlarged due to fat buildup within the liver cells, a person with fatty liver disease may experience mild discomfort or pain in the upper right side of the belly.

As reported by the Cleveland Clinic, other symptoms that may occur include nausea and loss of appetite, weight loss, jaundice (the skin and/or whites of the eyes turn yellow), and edema (swelling in the abdomen or legs from fluid retention). People with fatty liver disease may also become extremely fatigued, confused, and weak. More advanced diseases such as cirrhosis may lead to the following: portal hypertension (increased pressure within the portal vein that transports blood into the liver), enlarged spleen, kidney failure, intestinal bleeding, and liver cancer (via Johns Hopkins Medicine).

Causes and risk factors

Whereas the consumption of large amounts of alcohol is the obvious cause of alcoholic fatty liver disease, the cause of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is unknown, reports MedlinePlus. According to the NIH, NAFLD is strongly linked to both obesity as well as metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions (e.g., type 2 diabetes and high blood triglycerides) whose common denominator is insulin resistance. Roughly 75% of people with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes have NAFLD. These metabolic disorders cause fat to build up within liver cells via increased fat production in the liver or reduced mobilization (release into the circulation) of fat from the liver.

A 2020 study published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation suggests that the enhanced production of fat in the liver (rather than excretion of less fat) is the primary driver of NAFLD. The mechanism triggering greater fat syntheses in the liver was determined to be increased circulating levels of glucose and insulin resulting from insulin resistance. This is not unexpected, since elevated blood insulin promotes fat storage.

Apart from metabolic disorders, risk factors for NAFLD (per MedlinePlus) include being middle aged or older, being Hispanic or a non-Hispanic white (the condition is less commonly observed in African Americans), having high blood pressure, taking specific drugs (e.g., corticosteroids) and some chemotherapy medications, rapid weight loss, some infections (e.g., hepatitis C), toxin exposure, and obstructive sleep apnea (via the Mayo Clinic).

Stage 1: Simple fatty liver

According to a 2014 study in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, the first stage of both alcoholic fatty liver disease and NAFLD occurs when fat begins to collect in the liver (simple steatosis) due to heavy alcohol use and excessive food consumption, respectively. This stage is generally considered benign, since it is often asymptomatic and reversible.

However, a 2020 review published in Cells challenges this belief. While people with various metabolic diseases are at risk for developing NAFLD, the reverse is also true. Simple fatty liver disease carries an increased risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other components of the metabolic syndrome. Moreover, close to 25% of people with simple fatty liver will progress to the advanced stage of fibrosis (stage 3).

The type of fat that accumulates in the liver plays a crucial role in the disease's potential progression. Whereas saturated fats are associated with liver damage, unsaturated fats (e.g., oleic acid) appear to be protective against the toxic effects of fat in the liver. A fatty liver causes excessive production of reactive free radicals that can injure and destroy the body's cells, including liver cells. Patients are also more susceptible to drug-induced liver injury than healthy individuals. Furthermore, chronic alcohol consumption can speed up progression to inflammatory disease. Finally, in a 2020 study published in the Journal of Hepatology, patients with NAFLD who had Covid-19 were found to have a greater risk of Covid-19 progressing to a more severe disease than people without NAFLD.

Stage 2: Fat build-up with inflammation

Adding to the burden of excess fat buildup in the liver, inflammation is a hallmark of the second stage of both types of fatty liver disease: alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), per a review of studies published in the journal Gut and Liver. Inflammation occurs as a result of the body's attempt to heal and repair damaged cells, including liver cells. Liver inflammation is marked by the influx of certain white blood cells, or immune cells, to the damaged area, as well as by the recruitment of proinflammatory chemicals called cytokines. These cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha, or TNF-alpha) exacerbate the already-present inflammation and cause further degeneration of liver cells.

Inflammation in stage 2 fatty liver disease plays a major role in its progression to fibrosis (scarring), cirrhosis, and liver cancer (via an NIH report). Several harmful processes occurring in the body that contribute to inflammation and liver damage in people with fatty liver disease have been identified. These destructive processes include increased production of noxious free radicals; damage to DNA, proteins and cell membranes caused by free radicals; malfunctioning mitochondria (the cell's energy factory); defective autophagy (breaking down old or damaged cells to regenerate newer, healthier cells); and imbalanced gut flora.

Stage 3: Fibrosis

Fibrosis, the third stage of fatty liver disease, occurs when the body's healing and repair process in the liver becomes excessive, resulting in the formation of a large amount of persistent scar tissue to replace healthy liver tissue (via the Merck Manual). Early on, fibrosis is reversible, provided the cause is determined and resolved. However, if the underlying condition is not corrected and the liver is damaged over and over again, scar tissue can eventually disrupt the liver's architecture and function. Blood flow into and out of the liver may be obstructed by scarring, restricting the liver's blood supply and causing cell death as well as further progression of fibrosis. In addition, portal hypertension may ensue due to elevated blood pressure in the portal vein that transports blood from the gastrointestinal tract to the liver. The liver's ability to purify blood, store energy, and clear infections may also be compromised (via Medical News Today).

According to a 2017 review published in Gut and Liver, the scar tissue formed via fibrosis is essentially an amassing of huge amounts of abnormal connective tissue that includes collagen. At the same time, certain enzymes that degrade connective tissue may be inhibited, thus impeding the liver's ability to clear away the excess scar tissue. If fibrosis is sustained over many years (per a 2021 study review published in Frontiers in Medicine), it can lead to cirrhosis and liver-related disease and death. In fact, progressive liver fibrosis is the leading determinant of overall death.

Stage 4: Cirrhosis

As described by the NIH, cirrhosis occurs when fibrosis progresses over time to the point when most of the liver tissue is scarred. Cirrhosis can be either compensated or decompensated. In compensated cirrhosis, the liver is still functioning normally and there are usually no symptoms. Decompensated cirrhosis, in contrast, is marked by loss of liver function and portal hypertension, along with a wide variety of complications. It can be fatal.

For the most part, reports the Mayo Clinic, the liver damage from cirrhosis cannot be reversed. However, early diagnosis and treatment may minimize further damage. Cirrhosis is associated with several serious complications, including portal hypertension (elevated blood pressure in the portal vein that supplies blood to the liver); swollen abdomen and legs from fluid retention; enlarged spleen from portal hypertension; bleeding in veins that become enlarged from portal hypertension; infections; malnutrition; hepatic encephalopathy (impaired brain function due to inability of liver to remove toxins from the blood); jaundice (yellowing of skin and whites of the eyes and darkened urine, from uncleared bilirubin); diminished bone strength and higher risk of fractures; higher risk of liver cancer; and multiorgan failure in some people (this is still poorly understood).

For patients with decompensated cirrhosis who are unresponsive to medical treatment, liver transplantation may be an option (via the NIH). Around 85% of liver transplant patients survive for one year, whereas roughly 72% survive for five years.

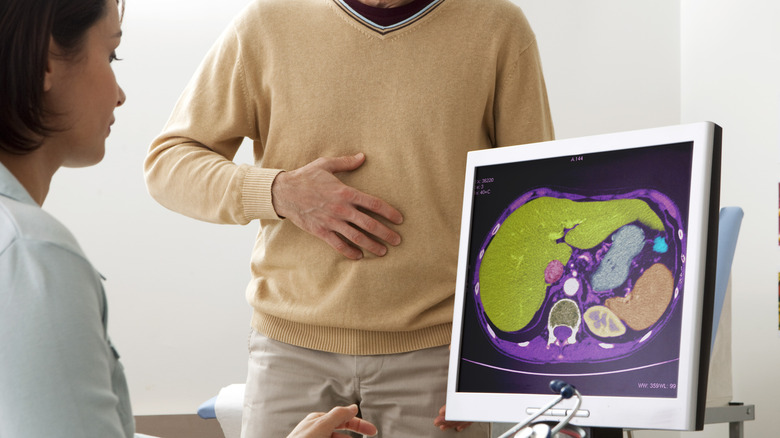

Diagnosis

Since most people with fatty liver disease are asymptomatic, the condition may be initially detected through a medical check-up for another disorder, per the Cleveland Clinic. Even most routine blood tests include liver enzymes, which, when elevated may alert your doctor that you may have liver damage.

Your doctor may then consider using some of the following diagnostic criteria (via WebMD). First, a history of alcohol use can help distinguish between alcoholic fatty liver disease and NAFLD. Information related to medication use, diet and other conditions is also important. A physical exam may also be conducted; this includes assessment of body weight and signs of disease such as jaundice and enlarged liver. If not already done, blood testing for high levels of liver enzymes could indicate liver abnormalities. Examples of liver enzymes are alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) scans, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be performed to detect fat in the liver. However, they cannot differentiate simple fatty liver disease from steatohepatitis (stage 2 liver disease).

Lastly, a liver biopsy (tissue sample) may be advised to determine whether the liver has inflammation or damage. It is used to diagnose more advanced liver disease when suggested by other forms of testing. Alternatively, as described in a 2021 study published in Cureus, a new noninvasive type of ultrasound called FibroScan may be used instead of a liver biopsy to determine the amount of fat and degree of fibrosis in the liver.

Treatment

Treatment of fatty liver disease is primarily directed towards eliminating the cause or keeping it under control (via the Merck Manual). People with fatty liver disease should aim to lose weight (a weight loss of 5% reduces fat in the liver, a 7% drop may lessen inflammation, and a 10% reduction is associated with regression of scarring and fibrosis), manage blood sugar levels (for diabetics), reduce blood levels of triglycerides, discontinue drugs that may induce or promote fatty liver, and avoid alcohol.

Other treatment options for fatty liver disease are detailed in a study review published in a 2017 edition of the World Journal of Gastroenterology. Corticosteroids improve survival rates overall, but 40% of patients with alcohol-induced liver disease do not respond to the drugs. Malnutrition increases the risk of infections and is very common among people with alcoholic fatty liver disease; thus, tube feeding has been shown to improve survival and reduce complications. PTX (pentoxifylline) reduces levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, and may be used as a treatment option when steroids are contraindicated. Liver transplantation is also an option; without it, patients with severe hepatitis have a 3-month mortality rate of 70%.

Thre are also optional therapies for NAFLD. Insulin sensitizers like metformin can help reverse insulin resistance, which is strongly linked to NAFLD. Meanwhile, lipid-lowering drugs are indicated for patients with elevated blood fats, and include gemfibrozil (e.g., Lopid) and statins (such as Lipitor). Eventually, combination therapies (rather than single therapeutic agents) may be required.

Best diet for fatty liver disease

The Mediterranean diet — which features generous amounts of fruits and vegetables, as well as healthy fats — is frequently advised by physicians for people with fatty liver disease, per the Cleveland Clinic. If weight loss is your goal, slow and steady is the way to go. Quick weight loss is not healthy, and may even worsen the disease.

As stated in a 2017 review of treatment options in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, a high carbohydrate diet that is particularly rich in fructose is the major driver of obesity, insulin resistance, and the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Accordingly, people with NAFLD should keep their sugar consumption below 10% of their total daily calorie intake, and avoid excessive consumption of fructose as well. Additionally, consumption of foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids such as fish and fish oil should be encouraged, while foods high in omega-6 fatty acids (e.g., seed oils) should be minimized. Omega-3 fats improve blood levels of lipids (fats) by enhancing fat burning, while also reducing fatty acid synthesis.

Finally, moderate exercise is also recommended as a necessary part of a healthy lifestyle. Indeed, in a 2007 study published in Digestive Diseases and Sciences, the combination of diet changes and exercise outperformed insulin-sensitizing drugs in their ability to lower elevated levels of the liver enzyme ALT in NAFLD patients.

Prevention of fatty liver disease

Prevention through lifestyle changes is always the best medicine. To evade alcoholic fatty liver disease, drink moderately. No more than one daily drink is advised for women and men over 65, while two drinks per day is the upper limit for men aged 65 and younger (via WebMD). Also, consult with your physician to ensure that drinking is safe when taking prescription medications. Some drugs such as acetaminophen may cause liver damage when taken while imbibing. Finally, refrain from behaviors such as IV drug use that increase you risk of contracting hepatitis C, a viral infection that increases your chances of developing cirrhosis if you drink.

To prevent NAFLD and the more advanced NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis), opt for a diet rich in fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats. Even some individual foods — garlic, coffee, leeks, asparagus, and probiotics — may help ward off fatty liver disease, reports Medical News Today. Lastly, complement a balanced diet with regular exercise. Aim for at least 2.5 hours of moderately intense exercise (e.g., biking) per week.