The Most Dangerous Health Trends Throughout History

We'd all love to stave off disease, stay healthy, lose weight, and get fit with a minimum of effort. That's just human nature. And doctors, likewise, are eager to find the easiest, most effective ways to help their patients. Unfortunately, these tendencies make it easy for anyone to buy into trends that seem helpful but actually endanger our health and even our lives.

Toxic tonics, risky surgeries, addictive medicines — in previous eras, when medical science was less advanced and fewer options were available, it's perhaps not surprising that people glommed on to scientific-sounding therapies that were shiny and new (and sometimes radioactive). But an examination of dubious health trends reveals that even in modern times, we can be too quick to accept solutions that are too good to be true.

In fact, as you're about to read, we tend to make the same misjudgments today that our ancestors did, whether it's discounting the addictive power of painkilling medicine or trying to lose weight by swallowing things we have no business swallowing. After you parse through this roster of erroneous remedies, ask yourself: What am I doing for my health today that might horrify my descendants tomorrow?

Drilling holes in the skull is an age-old medical treatment

Not only has the practice of drilling into someone's skull — a process called trepanation — been used by many different cultures around the world, it dates back to our Paleolithic ancestors. And it was still being used in some parts of the world in the 20th century (via BBC).

While the practice may have sometimes been performed ritualistically, trepanation seems to have often been used as a treatment for real illnesses. Records beginning in the 5th century BCE Greece reveal that it was mostly a treatment for head injuries, enabling skull fragments to be removed and "stagnant blood" to escape. Literature from ancient China suggests it treated serious headaches, according to Smithsonian magazine. In medieval Europe, trepanation became a misguided attempt to treat epilepsy or mental illness (via The MIT Press Reader). Even in ancient times, practitioners knew to be careful not to injure the brain, and patients who survived the procedure might live for years afterward. Ironically, once doctors started doing trepanation in hospitals, the survival rate plunged due to the likelihood of infection in pre-antiseptic years, per Smithsonian.

In case you're wondering, there are five main ways to perform trepanation, according to The MIT Press Reader — and none of them pleasant: scraping away the bone; making four intersecting cuts in the skull; cutting a circular groove and lifting off a disc of bone; drilling with a cylindrical saw; and drilling a circle of closely-spaced pinholes, then cutting the bone between them.

Bloodletting was a common medical practice for millennia

The idea that draining blood from the body will cure disease seems counterintuitive — even disturbing — to us today. But the concept remained a dominant one for 3,000 years, beginning in ancient Egypt and only falling out of favor in the 19th century (via British Columbia Medical Journal).

Bloodletting's rationale is based on the "four humors" theory of disease, dating back to Hippocrates, which declared that illness resulted from an imbalance of four fluids inside the body. Removing excess humors — usually blood, considered the dominant humor — was an attempt to correct that imbalance and restore health. Physicians developed specialized tools for this, including scalpel-like lancets (The Lancet remains the name of a prominent medical journal). Folding blades called "fleams" and even leeches were also used. Not only can a leech suck out 10 to 20 times its own weight in blood, it can be applied anywhere on the body without the need to find a vein. By the way, medical leeches are still occasionally used today (via Encyclopedia Britannica).

The fact that bloodletting remained so popular for so long, even after scientific discoveries cast it into doubt, is a case study in how medical treatments can be reinforced by social and economic forces. Like the overuse of antibiotics, some of today's practices may raise eyebrows a century from now, notes the BCMJ.

A fitness device was banned for causing hernias, paralysis, and miscarriages

Get thinner while you sleep? That was the promise of the Relax-a-Cizer, a gadget that hit the market in the 1950s. But the promise may seem less enticing when you realize you have to shock yourself in the process (via Gizmodo).

The Relax-a-Cizer operated by delivering an electric jolt to whatever muscles it was attached to, causing them to contract 40 times per minute. The idea was that this exercised and toned the affected muscles without you having to exert yourself. More than 400,000 of the devices were sold to people looking to relax and exercise at the same time. But as the sales climbed, so did the complaints.

In 1971, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration instituted a lawsuit against the device's distributors, Relaxacisor Inc. As revealed in an FDA press release following the trial, the judge determined that the Relax-a-Cizer "could cause miscarriages and could aggravate many pre-existing medical conditions, including hernia, ulcers, varicose veins and epilepsy." Relaxacisor Inc filed an appeal, which was denied, and the FDA recommended that all the devices be destroyed or rendered inoperable.

The device did have one final moment of fame, though, as a product that copywriter Peggy Olsen, played by Elisabeth Moss, worked on in an episode of "Mad Men."

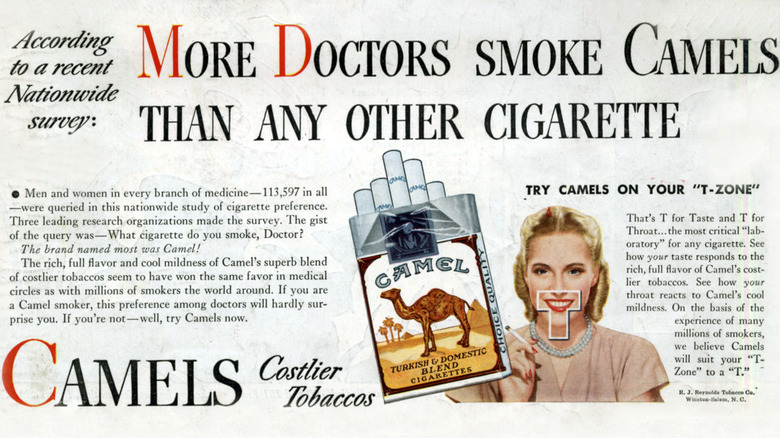

Doctors used to promote the health benefits of smoking

While advertising for cigarettes and other tobacco products is strictly regulated today, the situation was very different in the 1930s and 40s. Back then, smoking was the norm. Even most physicians smoked; as of 2006, less than 4% of U.S. doctors do, according to an article in the American Journal of Public Health.

In 1946, R.J. Reynolds launched a prominent ad campaign connecting cigarettes to health, claiming, "More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette." Physicians had been used in cigarette ads since the 1930s when Lucky Strike claimed that "20,679 physicians say 'Luckies are less irritating.'" Other ads suggested women could lose weight by reaching for a cigarette "instead of a sweet." Tobacco companies curried favor with the medical establishment by advertising in medical journals, recruiting medical researchers for marketing purposes, and, of course, giving out lots of free cigarettes.

There's a reason tobacco companies were so eager to get doctors on their side. Questions about the health effects of smoking had been raised as far back as the turn of the century and mounted in the decades that followed. Images of a kindly, white-coated family docs who smoked were an attempt to calm rising public anxiety about the safety of cigarettes. This strategy continued into the 1950s, when widely-publicized reports connecting cigarettes to lung cancer forced the tobacco companies to change their strategy. The tables had turned. Using physicians in cigarette ads would only remind people of the health concerns, rather than convince them that smoking was healthy, according to the American Journal of Public Health.

A weight loss supplement was banned for causing deaths

On the one hand, it helps you lose a bit of weight. On the other hand, people who take it are at increased risk for heart attack, seizure, stroke, and sudden death. That was the situation with ephedra, an herb also known as ma huang, prior to its 2004 ban by Food and Drug Administration. Extracts of the herb contained stimulant compounds called ephedrine alkaloids which were used in dietary supplements promoted for weight loss. But their dangerous side effects occurred even in people without preexisting heart disease or other medical problems. They were also linked to anxiety, dizziness, headache, nausea, and other symptoms, per the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

According to a CBS News report around the time of the FDA ban, concerns about the supplement's safety had already led to bans by several U.S. states, as well as the U.S. military, minor league baseball, the NFL, collegiate athletics programs, and the Olympic Committee. Many supplement makers had already stopped selling it. And in fact, its effectiveness as a weight-loss substance is questionable. It had only "modest short-term" effects on weight loss, according to a 2003 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Toxic mercury was used to treat syphilis

The sexually transmitted disease syphilis has a long history as a severe and stigmatizing illness. Outbreaks were often blamed on enemy countries. "Russians assigned the name of 'Polish disease', the Polish called it 'the German disease,'" according to an article published in the Journal of Medicine and Life. Other countries followed suit. In the centuries before penicillin and other antibiotic treatments were available, people infected with the syphilis bacterium faced a progressive illness that began with disfiguring rashes and could end with damage to the brain, eyes, heart, bones, and joints (via Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Given all that, it's perhaps not surprising that people who contracted the disease were willing to undergo difficult and dangerous treatments in hopes of a cure. Many of these methods involved ingesting purgatives and substances that would cause vomiting, diarrhea, urination, and sweating, all in an attempt to "clean" the blood. Beginning in the 16th century, the element mercury became a treatment of choice. It was administered in a topical cream, in a pill, by injection, and even inhaled as a vapor, per the Journal of Medicine and Life.

Unfortunately, mercury is extremely toxic, producing potentially fatal symptoms including paralysis, mouth ulcer and tooth loss, nerve damage, and kidney failure. Death from the treatment might be ascribed to the disease. And since syphilis can go into a dormant stage, it's hard to be sure the therapy had any real effect (via Journal of Military and Veterans' Health).

Lobotomies were used to treat mental illness

In its heyday, lobotomies were dubbed the "surgery of the soul" (via PBS). A more accurate description might be "sticking an ice pick into someone's brain." Nevertheless, it seemed like a revolutionary treatment for its time. Devised by a Portuguese neurosurgeon, the procedure involved surgically cutting into the prefrontal cortex of the brain to disrupt the nerve connections that were believed to be causing behavioral problems. Later, American physicians developed a non-surgical version: slipping an ice pick underneath the eyelid and through the eye socket, into the brain tissue (via American Association for the Advancement of Science).

In a time before medication and other modern tools for treating mental illness, lobotomy was seen as a godsend. As many as 40,000 Americans underwent the procedure, hundreds of them volunteering to have it done on themselves. The surgeon who developed the ice pick technique kept hundreds of letters sent to him by grateful patients.

Some lobotomy patients did improve; others remained unchanged, went into vegetative states, or died, reported NPR. Most lobotomy patients remained institutionalized, but the 30% or so who responded positively got all the publicity, per PBS. Over time lobotomy experienced mission creep, peddled not just as a last-resort therapy that might keep someone out of a nightmarish asylum, but as an intervention for everything from post-partum depression to problematic behavior in children (via Vice). It would take the rise of antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s to put the ice pick back in the kitchen drawer (via AAAS).

Arsenic was considered a health and beauty treatment

In the 9th century, even while known as a poison of choice for eliminating rats — not to mention rich relatives who've included you in their will — the chemical element arsenic was a popular ingredient for health and beauty treatments.

Though arsenic had long been used in some medicines, an arsenic craze was triggered by an 1851 medical journal article about a town in Austria where residents ate arsenic to "acquire a fresh complexion" or improve their breathing when exercising or working (via Ultimate History Project). The so-called "arsenic eaters" had developed a tolerance to the deadly toxin by consuming it in very small doses at first.

Many in the medical community were skeptical, but the arsenic genie was out of the poison bottle. After accounts of the "growing beauty" and "winning luster" imparted to Austrian peasant girls by arsenic, the chemical began appearing in everything from skin cream to soaps to drinkable tonics. Men were tempted by promises of developing the "strong sexual dispositions" of those lusty Austrians, per Gizmodo. There may not have been much actual arsenic in these products — fortunately, since arsenic is a cancer-causer as well as poisonous. But with so much of it around, it became a handy means of homicide. As arsenic became more associated with poisoning, it fell out of favor, even as scientific research called the whole idea of arsenic tolerance into question. By the 1920s, arsenic was back to being merely a deadly toxin.

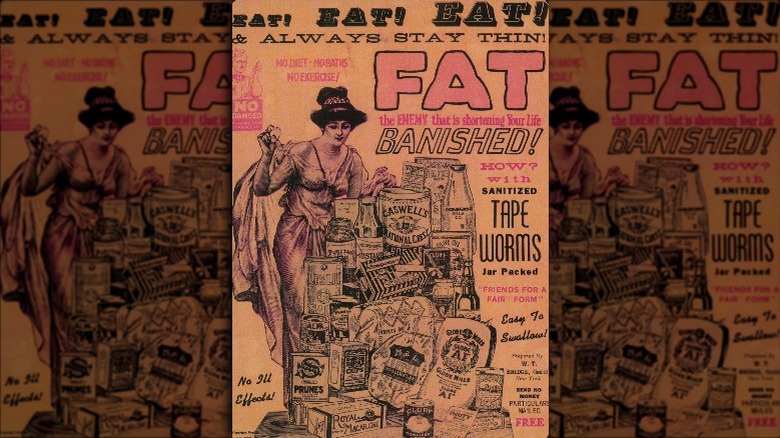

Growing a parasitic worm in your gut seemed like a reasonable way to lose weight

"Eat! Eat! Eat! And always stay thin!" Sound good? Maybe you should read the rest of this Victorian-era advertisement, which goes on to say: "How? With sanitized tape worms. Jar packed!"

The tapeworm is a flat, segmented, parasitic worm that grows inside your digestive tract, reaching a length of 50 feet or more as it absorbs nutrients from the food you're digesting (via Encyclopedia Britannica). But to Victorian women looking to lose weight, these parasites were also "friends for a fair form." The idea: Swallow a tapeworm egg, then help yourself to as many second helpings at the table as you want because the friendly monster inside you will siphon away excess calories. Reach your target weight, and then simply evict the worm — don't worry about how, a doctor will figure it out.

This concept was suspect for a few reasons. Number one: Ew. Also, a tapeworm infection can endanger the liver, lungs, brain, and bones. Few methods were available for dislodging a tapeworm, and they tended to involve dangerous practices like inserting a cylinder down one's throat. We can take comfort in knowing that there's a good chance that these treatments were shams, with no actual tapeworm eggs in them. The real danger was, and still is, that extreme weight loss practices normalize the idea that in the pursuit of unrealistic expectations of female beauty, any danger is worth it (via Atlas Obscura).

People drank radioactive water for health

Radium is a radioactive element first isolated by Marie and Pierre Curie in 1902 (via History). The strange properties of this energy-emitting new substance quickly captured the public imagination, and spurious claims of all sorts began to pop up: Radium could banish anemia. Radium could cure blindness. Radium could reverse aging. By 1911, influencers of the day could treat themselves to an "afternoon radium cure," basking in a spa-like setting that exposed them to the element's radiation, according to the Chicago Tribune. People who could afford it drank radium water, or even radium cocktails, and considered them an "elixir of life."

The radium honeymoon couldn't last forever, though. Deaths from exposure began to mount. The tragic case of the "Radium Girls," a group of women who were sickened by exposure to radium-containing luminous paint in the workplace, drew attention to the danger. But it took the 1932 death of a prominent steel mogul and dedicated radium water drinker to convince the U.S. government to crack down on radium flimflammery (via Chicago Tribune). Marie Curie would die two years later from leukemia after decades of exposure to radioactivity, per History.

Opium was used to treat everything from smallpox to teething pain

It all goes back to the "joy plant," as its Sumerians cultivators called it in 3400 BCE, aka the opium poppy. Extracts from this plant have been used as painkillers since the days of the ancient Greeks, if not earlier, according to PBS. In colonial America, people relied on a preparation called laudanum, an extract of opium mixed in alcohol, for relief from painful ailments like smallpox and cholera. Among its proponents was Thomas Jefferson (via Monticello).

By the 19th century, laudanum was being taken recreationally by literary figures like Byron, Keats, and Shelly (via British Library). Opium derivatives — including a new, more powerful extract called morphine — were included in all sorts of unregulated commercial products, from teething powders to menstrual cramp treatments to a "soothing syrup" that parents could use to calm fussy children, according to The Guardian. As the 20th century approached, the German company Bayer added another opium product to the marketplace. It was called heroin (via Drug Enforcement Administration Museum).

Eventually, the medical community began warning doctors about the dangers of addiction. The Federal government felt moved to act, passing anti-narcotic legislation that ended the easy availability of opium products. But the ban brought on other problems, reframing addiction as a criminal matter rather than a public health issue, and making it difficult for doctors to use opiates to help patients manage their addiction, per Smithsonian.

Opioid overuse created a public health crisis that's still with us

In October 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared a nationwide public health emergency "as a result of the consequences of the opioid crisis affecting our Nation." With the declaration came news that more than 140 Americans were dying every day from drug overdoses, most caused by opioids (via HHS.gov). The most recent statistics say that more than 10 million people misused prescription opioids in 2019.

The root of the crisis, according to the HHS, dates back to the 1990s, when pharmaceutical companies began encouraging doctors to prescribe more opioids — painkilling drugs derived from the poppy plant, or chemically related versions synthesized in the laboratory, per the Mayo Clinic. Despite drug makers' claims that new medications were not addictive, this proved not to be the case. As a result, the drugs were widely misused, and rates of death from overdosing surged (via Vice).

Some opioid users transition to heroin use, which has triggered a spread of disease related to injection drug use, like hepatitis C and HIV. Since the emergency declaration, the Federal government has been mobilizing resources to combat the crisis, including the multi-agency HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) initiative.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Did low-fat diets make Americans gain weight?

"This campaign to reduce fat in the diet has had some pretty disastrous consequences," public health expert Walter Willet told the PBS program Frontline. Research dating back to the 1940s suggested that reducing fat and cholesterol in the diet could lower heart disease risk in people who were at high risk. In the decades that followed, that message was adapted into U.S. dietary guidelines encouraging Americans to eat fewer high-fat foods. By 1984, a low-fat diet was being recommended for everyone to prevent obesity, even though skeptics in the research community were raising doubts.

The low-fat train had left the station. And physicians, the U.S. government, popular media, the food industry, and the general public were all on board. A new USDA food pyramid encouraged low-fat eating. The American Heart Association created a seal of approval for low-fat foods. Food makers cranked out low-fat packaged food that consumers wolfed down, not considering the calories they were getting.

So why did obesity rates surge? Critics claim that not only were low-fat diets ineffective and difficult to follow, they distracted from other important factors, like calories and exercise. And while Americans obsessed over fat, other forces — from high fructose corn syrup to rising car culture — tilted the scale towards obesity, as a report in the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences revealed.

People ate juice-soaked cotton balls to lose weight

In late 2013, reports began appearing in the media of a disturbing weight-loss tactic: dunking cotton balls in juice and swallowing them. The thinking was they'd make your stomach feel full and thus, you'd lose weight. According to ABC News, this strange "diet" trend started among fashion models before making its way to YouTube and other web outlets, gaining ground among tween and teenage girls.

As Women's Health noted, it should go without saying that this is a terrible idea. Cotton balls are not digestible; in fact, they're usually not even cotton. So swallowing them is just asking for a blocked digestive tract that will land you in the emergency room. On top of that, relying on minute amounts of juice for your calories sets you up for malnutrition.

And as Jezebel pointed out, it's hard to know how many people were actually doing this, and how much of the attention was due to the clickbait headlines it inspired. So maybe the bigger danger is that we fail to use stories like this to examine, as Jezebel calls it, "the horrific pressure on young girls to conform to a fashion industry body standard."