Tuberculosis Explained: Causes, Symptoms, And Treatment

Tuberculosis is a bacterial infection of the lungs that can also affect other organs such as the brain, spine, or kidneys, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tuberculosis is relatively rare in the U.S., with the CDC reporting that just under 8,000 Americans had active infections in 2021. In contrast, worldwide infection rates are much higher, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Recent data show that more than 10 million people, including 1.1 million children, became infected in 2020. At any given time, roughly a quarter of the world's population has tuberculosis. Eight countries account for two-thirds of all cases: India, China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and South Africa.

While many people with tuberculosis experience no symptoms, it causes serious health problems for others. As of recent years, tuberculosis is second only to COVID-19 on the list of deadliest infections worldwide (via WHO).

What causes tuberculosis?

A bacterium called Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) causes tuberculosis, according to the WHO. When people with an active tuberculosis infection in their lungs cough, sneeze, or spit, tiny droplets containing this bacterium spread into the air. People who inhale these droplets may become infected with tuberculosis, but not everyone who is exposed develops the disease. Tuberculosis usually spreads between close contacts, such as people sharing a household, rather than casual contacts like passersby at a bus stop or grocery store (per the American Lung Association).

Once inhaled, the droplets containing M. tuberculosis enter the lungs, where the bacteria become lodged in the lung tissue. In healthy people, their strong immune systems can typically prevent tuberculosis cells from growing. But people with weak or compromised immune systems will have trouble battling the infection. The cells quickly grow in the lungs, then move through the bloodstream and lymphatic system to other parts of the body including the bones, brain, spine, skin, kidneys, and lymph nodes. The tuberculosis cells will divide and grow in these areas as well, damaging healthy tissue and causing the symptoms of tuberculosis.

Symptoms of active tuberculosis

People who develop an active tuberculosis infection will feel sick, with some specific symptoms relating to the part of the body where the bacteria are growing. According to the Mayo Clinic, some symptoms of tuberculosis include fever, chills, fatigue, and night sweats. People with tuberculosis may also experience a loss of appetite and unexplained weight loss. Because many viral and bacterial infections cause similar symptoms, these symptoms do not necessarily indicate a tuberculosis infection.

Other symptoms show that tuberculosis is present and growing in the lungs. Tuberculosis patients may start coughing up blood, have a lingering cough that lasts for three weeks or more, and feel chest pain or pain when breathing or coughing. If the infection has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones, patients may feel pain or other symptoms in the infected organs. For instance, bloody urine can indicate a tuberculosis infection in your kidneys.

Some strains of tuberculosis are resistant to drugs

Over time, some strains of tuberculosis have become resistant to treatment, which means that some M. tuberculosis cells are not affected by antibiotics that normally kill tuberculosis germs. Drug-resistant tuberculosis can develop when people start treatment, then stop taking their medication before completing the prescribed course, which is why it is so important to finish antibiotics. According to Healthline, there are now tuberculosis strains resistant to first-line drugs such as isoniazid and rifampin, and others are resistant to both first- and second-line treatments. These strains are becoming a greater health problem worldwide.

Drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis are more difficult to treat, especially if the strain is resistant to more than one drug or if the patient has a weak or compromised immune system. When treating drug-resistant tuberculosis, doctors may have to rely on medications that cause more serious side effects. They may also have to prescribe treatments that last much longer than the standard four to nine months. Patients should finish their prescribed course of treatment to prevent the development of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Two types of tuberculosis infection

Tuberculosis infections can be latent or active, as the Mayo Clinic notes. Latent infections are those infections in which the M. tuberculosis bacteria has entered the lungs, but a healthy immune system has prevented it from growing. People with latent infections cannot spread tuberculosis to others. Active infections are those infections in which the bacteria are growing (via CDC).

Active infections pose a greater health problem because as the bacteria grows, it spreads to other parts of the body, damaging healthy tissue. Only people with active infections are contagious. Because tuberculosis cells are growing in their lungs, these patients release germs when they cough, talk, or laugh (via Wisconsin Department of Health Services). Latent infections can become active, sometimes months or years after the initial exposure to tuberculosis, when the patient's immune system can no longer fight off the germs and keep their growth in check. For this reason, it is important to diagnose and treat all infections, including latent infections, to prevent further spread of this disease.

Who is at risk of contracting tuberculosis?

Certain groups of people are at higher risk of contracting tuberculosis than others. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, people who are regularly exposed to an infected person (or people) at home or work have an elevated chance of becoming infected themselves. Certain settings also put people at high risk of exposure to tuberculosis. Simply living in a country with high rates of tuberculosis increases the risk of contracting this disease, as does living in a group setting such as a nursing home, homeless shelter, or prison. People who work with these high-risk populations are also more susceptible.

Certain health conditions weaken or suppress the immune system, making people with these conditions more vulnerable to tuberculosis infection. Drug and alcohol abuse weaken the immune system, so people with substance abuse problems are more prone to contracting tuberculosis. Infections such as HIV also lower an individual's resistance to infection. Other conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease, and certain cancers weaken the immune system. In other cases, treatments for certain conditions leave the patient vulnerable to tuberculosis. People who take immunosuppressant drugs after an organ transplant or for autoimmune conditions such as Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis are also at high risk, according to the CDC.

Who should be screened for tuberculosis?

Screening programs to identify people who should be tested for tuberculosis can help prevent the spread of this disease. Because tuberculosis rates are low overall in the United States, not everyone needs to be screened. The CDC recommends screening healthcare workers, not the general population, as a front-line strategy. Employers should screen all healthcare workers when they are hired. After that, only workers exposed to tuberculosis or who are at greater risk of exposure, such as respiratory therapists, pulmonologists, or emergency room workers, require continued screening.

The CDC recommends a simple questionnaire to screen healthcare works for their risk of developing tuberculosis. It asks if they have lived for one month or more in a country with high tuberculosis rates, have come in close contact with someone with infectious tuberculosis since the last time they were tested, or if they have a suppressed immune system because of HIV infection or treatment with TNF-alpha antagonists, chronic steroids, or other immunosuppressive medications. Anyone who answers yes to one or more of these questions should be tested.

Who should be tested for tuberculosis?

Healthcare workers identified through screening programs should be tested for tuberculosis (via CDC), as should anyone who is at high risk of developing the disease. Johns Hopkins Medicine recommends testing with either a skin or blood test. Both tests are relatively painless, can be performed at an outpatient visit, and provide quick results. People with positive skin or blood tests will need additional tests to confirm the results and provide more information.

When deciding whom to test for this disease, special considerations apply to children. Children, especially children younger than 4, have weaker immune systems than adults, so tuberculosis progresses more quickly in infected children. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends testing children who were exposed to infectious tuberculosis, are suspected of having tuberculosis, are at risk of progressing from latent to active tuberculosis, have an immunosuppressive disease, are about to start immunosuppressive therapy, or have at least one risk factor, such as being born in a country with high tuberculosis rates, for tuberculosis.

Initial testing for tuberculosis

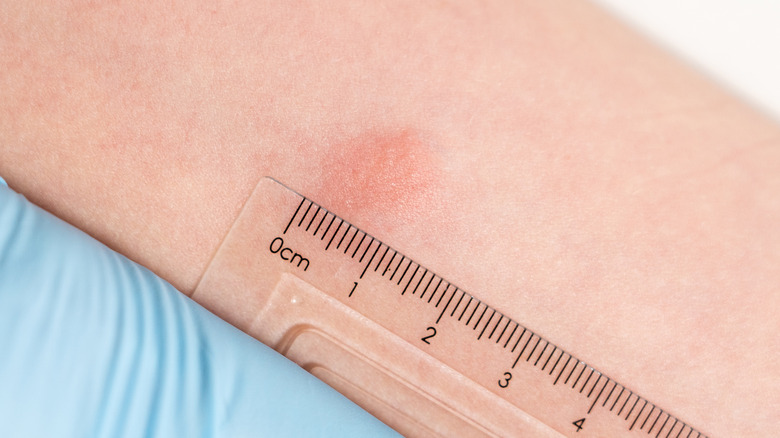

There are two types of initial testing for tuberculosis: skin testing and blood testing. The CDC describes both tests and the pros and cons of each. The tuberculosis skin test involves injecting a small amount of tuberculin fluid, which contains proteins from M. tuberculosis, under the skin of the forearm. The patient returns after 48 to 72 hours for an interpretation of the results. A positive result shows up as a hard, raised area. The skin test is a good choice for children under age 5, but it does have some drawbacks. It does not distinguish between latent, active, or previous infections, and anyone who has had a positive tuberculosis diagnosis will always test positive with this test. In addition, the skin test is sensitive to proper injection and interpretation, so it can produce false negative results (per the CDC).

The tuberculosis blood test simply requires a blood sample that is sent to a lab for analysis. Because it requires just one visit, it is an easier procedure for people with busy schedules. Compared to the skin test, it is a better choice for anyone who has received the BCG vaccine, which may cause a false positive skin test. The BCG vaccine is a tuberculosis vaccine commonly given to children outside of the United States.

Further testing for people with positive tuberculosis results

People who test positive with either skin or blood tests require further testing to determine whether they have latent or active infections. According to the Mayo Clinic, doctors may recommend diagnostic imaging or sputum samples for people with positive tuberculosis results. Diagnostic imaging allows doctors to look at the lungs for evidence of tuberculosis infection. When the immune system detects M. tuberculosis, it may protect the body by walling off the bacteria, which will show up as white spots on the lungs. Chest X-rays and CT scans can detect these tuberculosis-specific changes in the lung tissue.

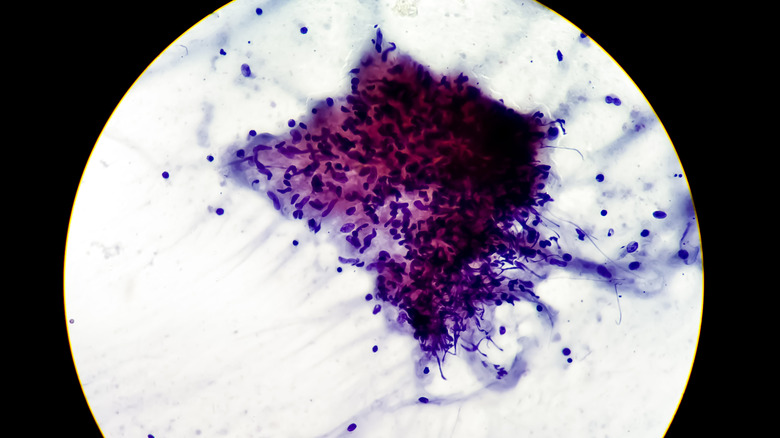

With a sputum sample, doctors can confirm the presence of M. tuberculosis bacteria in the lungs. The patient provides a sputum sample by coughing or spitting up sputum, a.k.a. mucus. Lab scientists then determine whether any tuberculosis bacteria are there. If so, they can determine the specific strain the patient contracted, which can help doctors prescribe the best treatment.

Treatment for tuberculosis

Anyone with active tuberculosis and some people with latent tuberculosis require treatment. Antibiotics kill bacterial cells (via Healthline), including the M. tuberculosis cells that cause tuberculosis. If you develop tuberculosis, doctors may recommend a standard course of treatment, or they may recommend a tailored course specific to the strain of tuberculosis you contracted, especially if you are infected with a drug-resistant strain. All tuberculosis patients require antibiotic treatment for at least three months.

If you start a treatment, you must finish it, even if you feel better (via Healthline). Sometimes, people with tuberculosis stop taking their medication after a few weeks because their symptoms have improved or because they dislike the negative side effects. It takes months to kill all the tuberculosis cells in your body. While your symptoms may improve after a few weeks, there are still M. tuberculosis bacterial cells present. According to the WHO, drug-resistant strains develop when patients stop taking their medication prematurely.

Treating latent tuberculosis

Although people with latent tuberculosis infections experience no symptoms, they may still require treatment with antibiotics. Roughly 10% of latent tuberculosis will become active, sometimes not until months or years after the initial infection. When this happens, the patient will not only become sick and experience physical symptoms of tuberculosis infection, but they will also be able to spread it to others. Therefore, treating latent tuberculosis infections benefits both the patient and the public, according to the CDC.

People with latent infections who are at high risk of becoming active should be treated for at least three to four months with specific antibiotics (per the CDC). Doctors should confirm that the patient does not have an active infection before prescribing treatment. Three drugs are used to treat latent infections: isoniazid, rifapentine, and rifampin. Because patients are more likely to complete a short course of antibiotic treatment, doctors should prescribe the shortest treatment that will work for the patient's strain.

Treating active tuberculosis

People diagnosed with active tuberculosis require prompt treatment. Depending on their symptoms, patients may need to be hospitalized, or they may be well enough to start treatment at home. Traditionally, doctors prescribed a six- or nine-month course of a combination of antibiotics, including isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, for active tuberculosis infections, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. Patients typically cease to be contagious after a few weeks of treatment.

Researchers are always looking into new treatments for tuberculosis. Johns Hopkins Medicine reports that a study performed by Johns Hopkins University, the CDC, and the National Institutes for Health (NIH) found that four months of high-dose treatment with rifapentine and moxifloxacin was just as effective as longer treatments. A recent study in Nature Immunology found that proteins present in the lungs of tuberculosis patients are the same as proteins found in cancerous tumors, suggesting that drugs used to treat cancer may lead to better tuberculosis treatments.

Treating drug-resistant tuberculosis

Strains of tuberculosis that do not respond to first-line antibiotics are considered drug-resistant (per Healthline). Your doctor may suspect that you have drug-resistant tuberculosis if your symptoms do not improve with treatment. While challenging, it is still possible to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis.

The first step in treating drug-resistant tuberculosis is to test a sample of bacteria to determine which drugs your infection has developed a resistance to. That will let your doctor know which drugs to avoid. Some strains are resistant to just one type of antibiotics while others are multiply resistant. Next, your doctor may prescribe one or more antibiotics — they may choose a different first-line antibiotic or pursue another approach, such as fluoroquinolone or bedaquiline-linezolid-pretomanid combination therapy.

Doctors reserve fluoroquinolone for when other options fail because this drug can lead to permanent muscle, joint, and nervous system damage. Likewise, the FDA approved bedaquiline-linezolid-pretomanid combination therapy only for extensively drug-resistant, treatment-intolerant, or nonresponsive multidrug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis because it can cause peripheral neuropathy, anemia, visual impairment, and other side effects. Contact your doctor immediately if you experience any unpleasant side effects.

Tuberculosis is highly contagious

Tuberculosis is highly contagious (via Everyday Health), but just because you are exposed to it does not mean that you will contract it. According to the WHO, even people who are infected with tuberculosis have just a 5-10% chance of becoming sick. By following certain precautions, people with tuberculosis can take steps to prevent spreading it to those around them.

According to the Mayo Clinic, people who have an active tuberculosis infection can stop the spread by staying home during the first three weeks of treatment and avoiding contact with other people. When they must be near others, they should keep the rooms well-ventilated by opening windows and wear a mask. Because M. tuberculosis spreads through the droplets expelled from the mouth and nose, patients should take extra care when coughing or sneezing. They should cover the mouth and nose with a tissue, then seal the contaminated tissue in a plastic bag and throw it away.