Dementia Explained: Causes, Symptoms, And Treatments

The prevalence of dementia — a condition that causes a decline in cognitive functioning – has decreased over the past decade or so. According to PRB, the number of people with dementia has dropped between 1% and 2.5% per year in recent years, but that doesn't account for the baby boomers who are getting ready to reach prime dementia age. Data predicts that by 2040, more than 12 million Americans could be diagnosed with some form of dementia.

Despite lowering numbers right now, dementia still has a lot of unknowns that are important to figure out. Alzheimer's Disease International points out that most people with dementia have never been formally diagnosed, making them unable to access the care they might need. Filling in these gaps could improve dementia care overall, although there's currently no treatment for the condition. Continue reading to learn more about dementia, how it happens, and how people with dementia can benefit from therapies, lifestyle changes, and the right care plans.

The different types of dementia

When you think of dementia, Alzheimer's disease is probably what first comes to your mind. Granted, it is the most common form of dementia, affecting as much as 80% of people living with dementia (per the Alzheimer's Association). Alzheimer's typically affects people 65 and older and can worsen quickly, with individuals usually living an average of 4-8 years after diagnosis.

However, Alzheimer's isn't the only form of dementia. Agespace says that more than 400 types exist, and those diseases are what technically cause dementia. In addition to Alzheimer's, vascular dementia — caused by a lack of oxygen to the brain — is a common type. Dementia with Lewy bodies can happen when Lewy body proteins reach unhealthy levels in the body, and frontotemporal dementia is caused by damaged brain cells that affect the frontotemporal lobes.

Healthline adds that some people end up with more than one type of dementia, known as mixed dementia. However, it's not uncommon for individuals with mixed dementia to be unaware that they have an additional form of dementia.

What are the common causes of dementia?

Dementia can be caused by various brain-affecting conditions, like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. These conditions create changes in the brain that influence cognitive function, typically leading to a cognitive decline (per Stanford Health Care). But, what causes these conditions? Each form of dementia has different causes, hence why they're diagnosed and named differently. For instance, a single stroke, several mini-strokes, or narrowed blood vessels could cause vascular dementia (via the NHS).

The most common cause of dementia is the progression of Alzheimer's disease (per the National Institute on Aging). Experts believe that a buildup of proteins known as neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques causes Alzheimer's disease. The excess proteins affect the brain in many ways, causing changes that kill neurons and shrink the brain, preventing it from making the connections it needs for cognitive thinking and functioning. In later stages of Alzheimer's, brain tissue becomes much smaller, leading to severe symptoms.

Less common causes of dementia

Less common conditions can also cause dementia, especially as they progress in severity and cause more damage to the brain. According to the NHS, corticobasal degeneration (CD) affects both the cortex and basal ganglia of the brain, primarily affecting movement. However, as the disease progresses, it can cause dementia symptoms. Another rare cause of dementia is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). CJD can progress very slowly or quickly, depending on its cause, and its symptoms can mimic those of vascular dementia or Alzheimer's.

There may also be some genetic implications for dementia risk, per the Alzheimer's Society, which states that about one-quarter of people aged 55 or older are closely genetically related to someone with dementia. When complex diseases cause someone's dementia, it's possible that both lifestyle and genetic factors play a role. Some families can share the same risk factors for the complex disease that caused dementia. In rarer cases, single genes can influence the development of dementia, often causing dementia that occurs early in life.

Risk factors for dementia

You might wonder why it seems that some families have more instances of dementia than others. Over the decades of research surrounding the causes of dementia, experts have found several risk factors that help us determine who might be more at risk for developing some form of dementia.

According to the Alzheimer's Society, risk factors can increase the likelihood that someone gets dementia, although having a risk factor does not automatically mean they will develop it. Some risk factors for dementia — unhealthy lifestyle choices like excessive alcohol usage or smoking, for example — are avoidable. However, others aren't. For instance, aging is a risk factor for dementia, and it's something we can't avoid. Reaching age 65 increases the chances of developing dementia. Familial genes that are passed down from generation to generation can also cause dementia. Women, Black African, Black Caribbean, and South Asian groups are also likelier to develop dementia than other groups. Additionally, certain conditions such as depression, cardiovascular disease, and middle-aged hearing loss have been linked to a higher risk for dementia.

A 2022 study published in Geriatrics also found a potential link between walking gait and dementia risk. Data from more than 16,000 participants found that people experiencing both a slowed gait and cognitive decline had a significantly higher risk of developing dementia than those who didn't experience the dual decline of gait and cognition.

Early signs of dementia

Dementia occurs in stages. Although the early stages may not be as noticeable in some people as in others, they still happen. However, some people might experience each stage more rapidly than others, also known as rapidly progressive dementias. In these cases, dementia can be extremely difficult to diagnose compared to cases that progress more slowly.

In the early stages of dementia, one of the first signs is usually forgetfulness and memory loss. People with early dementia might ask the same questions repeatedly, forgetting that they already asked them, or need to write down all important dates and appointments to avoid forgetting them. During the earlier period, people might also have difficulty planning things, get confused about times and places, and struggle to name familiar items. Dementia also often comes with poor judgment, which can lead to a lack of hygiene or taking care of necessary day-to-day tasks (via the Alzheimer's Association).

What happens in the later stages of dementia?

In the mid to late stages of dementia, a person's symptoms have likely begun affecting their lives enough to lead to a diagnosis. By the latest stages of the condition, people with dementia usually require extra care that might involve communication help, nursing care, and assistance with their daily needs (per the Alzheimer's Association).

Common signs that a person has reached this stage of their condition include a progressive loss of memory — often to the point of not recognizing those closest to them, even if just occasionally — a decreased ability to write or speak effectively, and difficulty eating. People with dementia often experience physical challenges during this stage as well, affecting their ability to care for themselves, walk, or get in and out of bed (via Dementia Australia).

By this point, it's usually necessary for a close family member or caregiver to step in to help people with dementia. The National Institute on Aging explains that caregivers become vital in the end-of-life process for dementia patients, taking care of everything from medication refills to important health decisions regarding treatments and quality care.

Evaluations for dementia diagnosis

In addition to reviewing a patient's medical history, medical professionals can diagnose dementia using evaluations and tests. Evaluations may consist of psychological and psychiatric evaluations. Doctors may also enlist the help of a caregiver or close family member to talk about any recent changes in the patient's health or events that could be leading to memory loss and other symptoms (per Stanford Health Care).

To evaluate dementia, medical professionals refer to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed., which outlines the criteria for cognitive impairment and dementia (via American Family Physician). They may use various assessments and evaluations to rule out other conditions and determine dementia as the primary cause of symptoms. Potential cognitive evaluation tools include the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition, and a Mini-Cog test. Often, doctors use a combination of evaluations to get a full picture of the person's symptoms and cognition. Then, they refer to the diagnostic criteria, which determine minor and major neurocognitive disorders based on how much a person's symptoms interfere with their daily life.

Testing for dementia

Aside from psychological evaluations, medical professionals can also rely on various forms of testing to detect and diagnose possible dementia. A doctor might first start with blood work, which can rule out conditions that can cause symptoms of dementia (such as thyroid imbalance) or conditions that can also affect the brain (such as infections). The blood testing might also look for infections like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which can lead to dementia (via Stanford Health Care).

More in-depth testing may require brain scans to take a closer look at the brain and any issues that could be causing a person's symptoms. As mentioned, a person who has dementia may have shrunken brain tissue, so their brains can appear differently on brain scans than a person's brain without signs of dementia. The scans may also pick up strokes or tumors that cause dementia and abnormalities in the structure of the brain, a common sign of Alzheimer's.

Medications for dementia

Currently, there are no cures for dementia, but medical professionals can assist patients with dementia through various types of care, therapies, suggestions for lifestyle changes, and medication. Many medications don't directly manage dementia, but instead can make symptoms more manageable. For example, a patient might take medication for behavioral symptoms, like anxiety, aggression, or depression. Others might need medication for heart problems or stroke prevention (via the NHS).

Some medications target cognition-related symptoms of dementia. Cholinesterase inhibitors prevent the body from breaking down a chemical that assists with memory, which could improve a patient's cognitive skills, like communication and thinking (via the Alzheimer's Association). Different versions of these medications are available for patients in any stage of Alzheimer's disease. People with severe symptoms may also use glutamate regulators, which assist the brain's ability to process information by regulating the chemical glutamate. Combinations of these medications are also prescribed to some patients, typically those with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's.

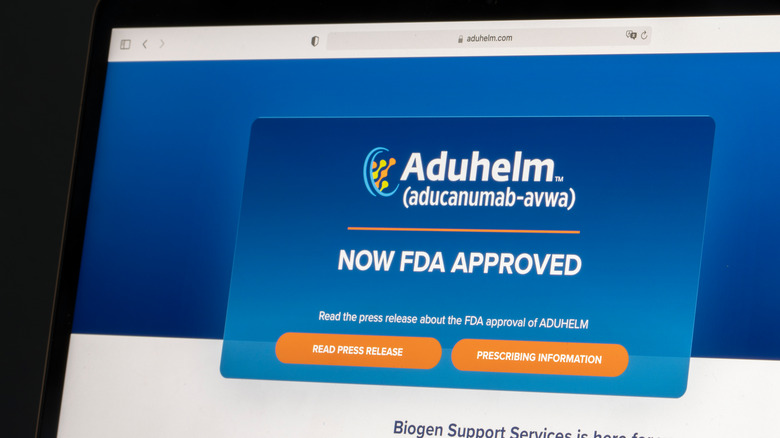

There's now an FDA-approved therapy for Alzheimer's disease

While most medications can improve symptoms relating to Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia, aducanumab is the first FDA-approved drug that could slow down the progression of Alzheimer's. According to the Alzheimer's Association, the drug works by targeting the production of beta-amyloid plaques that cause the disease. More specifically, it removes some beta-amyloid from the body to prevent them from turning into plaques.

The approval for Aduhelm, the brand name for the drug, happened in 2021 through an accelerated approval process, allowing it to be used as an Alzheimer's treatment. The FDA still required a post-approval trial to ensure its benefits, but remained hopeful that the drug could improve the lives of people with the disease. According to the director of the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Patrizia Cavazzoni (via the FDA), "This treatment option is the first therapy to target and affect the underlying disease process of Alzheimer's. As we have learned from the fight against cancer, the accelerated approval pathway can bring therapies to patients faster while spurring more research and innovation."

How palliative care helps people with dementia

Because there's currently no cure for dementia, much of the treatment surrounding the condition focuses on quality care. Palliative care is a type of care designed to improve a patient's quality of life when they're facing a serious medical condition. In the case of dementia, palliative care can help individuals complete their daily tasks, like getting dressed, taking a shower, and eating dinner. Palliative care can take place in a person's home or, if the person needs the help of a nursing team, in a skilled nursing facility.

Palliative care is also designed to support the family of a person living with dementia. Through this type of care, family members can find relief for some of the stresses of caregiving, get resources to help understand what their family member is going through, and see that their loved one is being cared for in the ways they need. One study published in BMC Palliative Care found that family members most appreciated their loved ones getting relief from pain and suffering and the empathy and attention the family received from the palliative care team during the care period of their loved ones.

Lifestyle changes could help manage (or prevent) dementia

Although there are not yet any connections between lifestyle changes and curing dementia, some experts believe that making certain changes could improve dementia symptoms and quality of life. For example, creating a calming environment for a person with dementia could reduce the risk of confusion and subsequent aggression or upset. And, helping a person with dementia stay as active as possible could boost mental and physical health (via Beth Israel Lahey Health).

The lifestyle you lead before developing dementia could also influence the risk later on, research finds. One 2020 study (via NIH) found that certain lifestyles, like those of non-smokers or physically active people, could lower the risk of developing Alzheimer's later in life by as much as 60%. Participating in active cognition activities, following a Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet, and limiting alcohol consumption could also play a role. The results of the study noted the most significant benefits for people who committed to at least four of the five lifestyle factors.

Behavioral therapy for dementia

Dementia can cause several behavioral changes in a person, even in its earliest stages. Most commonly, anxiety, depression, and irritability take over. In the later stages of dementia, someone might have more emotional outbursts, hallucinations, and aggression. Changes in routine, a move to a new care facility, or being asked to complete a task like eating could easily provoke someone with dementia (per Alzheimer's Association).

That's why behavioral therapy, which is often combined with other therapies and medications, could prove useful for patients with dementia. One study review published in the British Medical Journal (via NPR) found that behavioral therapy could be more effective for individuals with dementia than treatment with antipsychotic drugs. According to the review, treatments involving highly trained caregivers who offered planned activities and effective communication to patients were the ones that saw the best results. "Why I think the caregiver interventions work is because they train caregivers to look for the triggers of the symptoms," says lead researcher Helen Kales. "And when [caregivers] see the triggers of the symptoms, they train them to manage them...It's inherently patient- and caregiver-centered."

The outlook for patients with dementia

Although there isn't any cure for dementia yet, a commitment to awareness, advocacy, and research has led to some positive outlook changes, especially for individuals with Alzheimer's. In 2012, the National Plan to Address Alzheimer's set a series of goals and a plan to address those goals regarding research and funding for Alzheimer's (via the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke). Ten years later, the plan has brought about progress in identifying biomarkers of Alzheimer's and improving research technologies to continue learning more about the condition.

In 2020, a new blood test was released to identify dangerous levels of amyloid in the bloodstream that could predict whether a person could have amyloid plaques in the brain. Per the American Brain Foundation, this test has proven more accessible and affordable than previously used spinal fluid analysis to gain the same information. Dr. John C. Morris, the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center's director, calls the blood test a "potential game-changer."