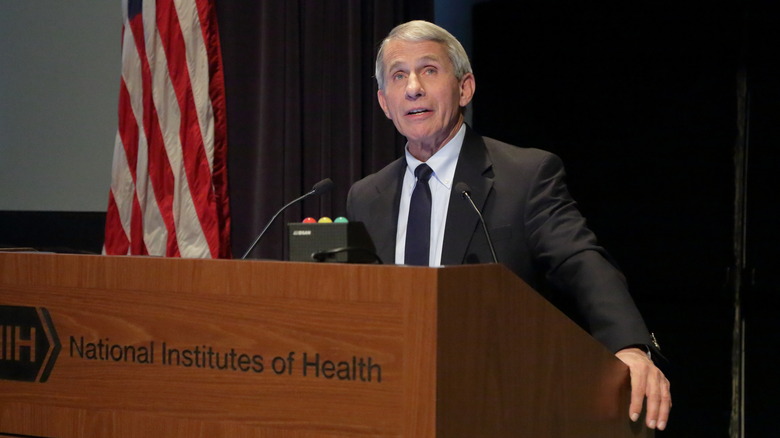

What You Didn't Know About Dr. Anthony Fauci

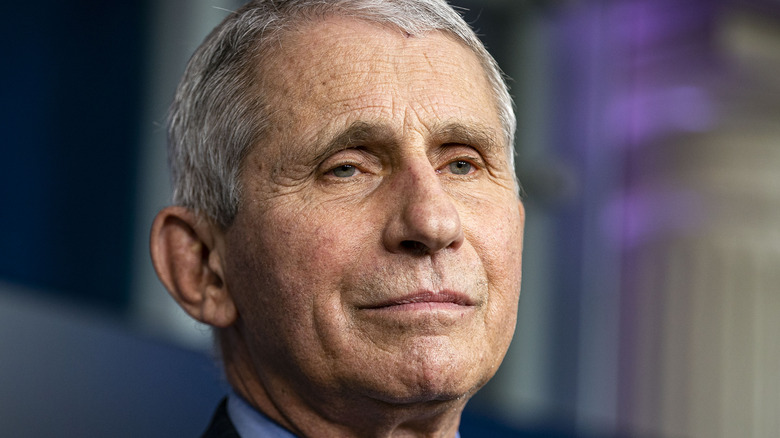

Dr. Anthony Fauci has become a household name as he's helped America navigate through COVID-19. He's the nation's top infectious disease expert and chief medical advisor on the coronavirus to President Joe Biden. In his trademark New York accent, he has an innate ability to make scientific information simple and understandable. His directness is also what sometimes makes him a polarizing figure. "I have stood for always making science, data, and evidence, be what we guide ourselves by," Fauci said in an interview with "Fox News Sunday" (via Yahoo News). "And I think people who feel differently, who have conspiracy theories, who deny reality, that's looking them straight in the eye."

Married for 36 years and a father of three, Fauci has advised seven U.S. presidents on domestic and global health issues (via Merck). He's guided us through numerous epidemics, and now the COVID-19 pandemic. Fauci has become a reluctant celebrity; his face appearing on an array of merchandise from coffee mugs, T-shirts and socks, to prayer candles and a bobblehead figure (via Vox). Yet there's much more to know about this accomplished physician-scientist.

He's the son of first generation Italian-American parents

You might think that it is only science that runs deep in the Fauci family tree. But interestingly, there are a lot of artists mixed in the branches as well. Recalled Dr. Anthony Fauci to The New Yorker, "Virtually all my relatives on my mother's side — her father, her brother, and her sister's children — are artists." In fact, his maternal grandfather, Giovanni Abys, painted landscapes and even did illustrations for Italian magazines, according to an article in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

As the Journal of Clinical Investigation highlights, Dr. Fauci's parents, Stephen and Eugenia, are first-generation New Yorkers. Their Italian parents emigrated from Naples and Sicily to the United States via Ellis Island at the end of the 19th century. Young Stephen and Eugenia grew up in lower Manhattan's Little Italy in New York City and went to public schools. They married straight out of high school at the age of 18, but both went on to college afterward. Stephen received a degree in pharmacy from Columbia University, while Eugenia graduated from Hunter College on the Upper East Side of New York City.

He grew up in Brooklyn

The Faucis settled in Bensonhurst, a working-class mostly Italian-American enclave in the southwestern side of Brooklyn (via Journal of Clinical Investigation). Young Anthony and his only sibling, Denise, spent their early childhood here (via the Brooklyn Reporter). Fauci described the neighborhood to the U.S. World Herald as "the kind of neighborhood that on every Sunday morning, a mother walks out on her porch and calls for Anthony, about 20 kids come running yelling 'What Mom?'" The community had strong ties with each other. "Literally the family was the neighborhood," he told The Washington Diplomat. He recalled it being filled with the music of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, and Sunday dinners meant a house full of aunts, cousins, and uncles, and tables filled with good food (via U.S. World Herald).

The family moved to adjacent Dyker Heights, where they lived in an apartment above their own store, Fauci Pharmacy (via Journal of Clinical Investigation). They all pitched in to run it; his pharmacist dad dispensed medications, his mother and sister worked behind the counter, and young Anthony delivered prescriptions on his Schwinn bicycle (via Holy Cross Magazine). Dr. Fauci told The Washington Diplomat that his father, who was a "non-materialistic, public service-type of person," wouldn't charge for medications when people couldn't afford them. "Go to your Walgreens or your CVS and try to walk out without paying for your prescription. See how far you get," he said. "But [my father] used to do that all the time. So we didn't make a lot of money at all. We just had enough to get along."

He was the captain of his high school's basketball team

Dr. Anthony Fauci attended Catholic schools, from Our Lady of Guadalupe in Brooklyn to the Jesuit-run, academically-rigorous Regis High School in Manhattan. He had to take a bus and three separate subway trains to get to the high school. "Students from every parochial grammar school in all the five boroughs of New York competed to receive admission [to Regis], making it highly competitive," he said in an interview for the National Institutes of Health.

Like so many kids his age, the future doctor was obsessed with sports. In his Brooklyn neighborhood, young Anthony played them all: basketball, baseball, and football. His heroes were the likes of Joe Di Maggio and Mickey Mantle. Little would he have guessed that decades later, in 2020, that his very own mug would be on a baseball trading card, throwing the ceremonial first pitch at the Washington Nationals and New York Yankees season opener. It would break sales records in a 24-hour period (via USA Today).

Legendary in its own way was his stint as captain of the 1958 Regis High School basketball team. Standing just 5 feet, 7 inches tall, he was a powerhouse point guard. The Wall Street Journal's Ben Cohen told WBUR, "[Fauci] was always short, but he always was this incredible leader. ... He was a great ball handler, an annoying defender. One of his teammates said that he would literally dribble through brick walls."

He was raised Catholic, but now considers himself a 'humanist'

With Dr. Anthony Fauci's strong Catholic roots, it might be surprising to learn that he doesn't consider himself a traditional Catholic these days. Fauci told Science magazine, "I am not a regular church attender. I have evolved into less a Roman Catholic religion person to someone who tries to keep a degree of spirituality about them. I look upon myself as a humanist. I have faith in the goodness of mankind" (via Religion News Service).

In a later interview with CSPAN, Fauci reaffirmed that, in essence, he believes in the goodness of humanity and not as much in the institution itself. "I think that there are a lot of things about organized religion that are unfortunate, and I tend to like to stay away from that and think more in terms of the principles that I learned from the Jesuits, from the Catholic religion, the principles that I run my life by," he explained.

In 2021, Fauci was awarded "Humanist of the Year" by the American Humanist Association, the organization's highest honor, for his "unwavering commitment to accessible, evidence-based information and his robust communication to people about public health issues." Past award recipients include astronomer and author Carl Sagan and trailblazing activist Gloria Steinem.

He's studied Latin, Greek, French, and philosophy

There was a point in his life when Dr. Anthony Fauci wasn't sure if he would go into medicine or the humanities. The classes at Regis High School emphasized the classics. "We took four years of Greek, four years of Latin, three years of French, ancient history, theology, etc," he told the National Institutes of Health.

A classmate described Fauci's impressive mastery of the Greek language to Holy Cross Magazine, saying, "When we were seniors, Tony and a group of students who were members of the Greek Academy would go to Yale and have discussions with the faculty on 'The Iliad' and 'The Odyssey'– in Greek. That sort of explains the brilliance of his mind."

Bachelor of Arts–Greek Classics–Premed was the track that Fauci chose at College of the Holy Cross, a private Jesuit-run liberal arts college in Worcester, Massachusetts, where the young scholar received his undergraduate degree. Fauci described the track as classics that were heavily weighted with philosophy, French, Greek, and Latin. This degree path was unusual, he told The New Yorker. "We took many credits of philosophy, everything from epistemology [the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion] to philosophical psychology, logic, etc. But we took enough biology and physics and science to get you into medical school." And indeed it did. Four years later he received his medical degree, first in his class, from Cornell University Medical College (via Britannica).

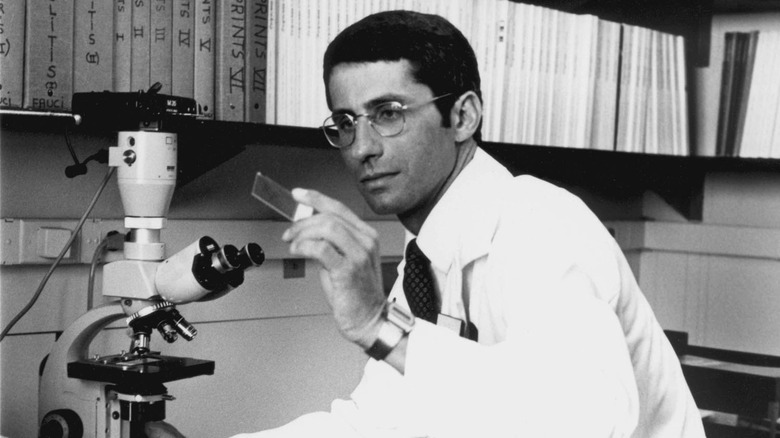

He's been the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984

With the Vietnam War raging on, medical school graduates in the '50s and '60s were required to do a stint in the armed forces or the Public Health Service, such as the NIH, CDC or FDA. "We were gathered in the auditorium at Cornell, early in our fourth year of medical school," he recalled to the The New Yorker, when a recruiter told the roomful of young men to make a choice and give their preferences. Fauci chose the public health route and was accepted into the NIH Associate Training Program, where he would participate in clinical and laboratory research that included primary patient care (via The NIH Catalyst).

"[The NIH was and still is] a very desirable place to be from the standpoint of people wanting to go into academic medicine. If you look historically over the years, the vast majority of leaders in biomedical research had some training, either a few years or many years, at the NIH," he said in an interview back in 1998 (via National Institutes of Health).

After finishing his medical degree and internship, Fauci began what would become a decades-long career at the NIH in 1968 — first as a clinical associate at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and ultimately taking the helm as NIAID's director in 1984, where he remains as of this writing (via Britannica).

He identified a cure for an autoimmune disease

When Dr. Anthony Fauci was leading the NIAID's clinical physiology section in 1974, some of his patients were presenting with a rare inflammatory condition called vasculitis, an autoimmune disorder. In this once fatal disease, the body attacks its own blood vessels causing vital organs to shut down (via WBUR).

Since many of Fauci's patients were undergoing chemotherapy for cancer, he would routinely consult with physicians at the National Cancer Institute, which shared the same building as his lab. Chemotherapy drugs target cancerous cells but the high doses needed also wreak havoc on the body's immune system, making it susceptible to infection (via American Cancer Society). Fauci wondered if he could use those same chemotherapy treatments at lower doses on his vasculitis patients to tamp down their overactive immune response (via Academy of Achievement). As it turns out, this was a really good idea.

"Much to our delight, [our patients] had a total remission. Before you know it, we ended up curing a very, very lethal, albeit uncommon, disease," said Fauci to The New Yorker.

He was at the forefront of HIV/AIDS research in the 1980s and '90s

It was in a CDC publication when Dr. Anthony Fauci first read about five gay men in Los Angeles getting a rare type of pneumonia (via CSPAN). Then it jumped to 26 gay men in more cities with the same pneumonia, plus a rare cancer that "you only see in people who are immunosuppressed," he said.

A new virus, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), was gnawing away at the human immune system. "[In 1981] I submitted [an article about the disease] to a major journal. They rejected it because one of the reviewers said I was being too alarmist," he recalled in the 2021 Disney Plus documentary, "Fauci" (via Eat This, Not That!). Government response was slow and the LGBT community was angry. Years dragged on. Protests erupted, even on the NIH campus, and Fauci was the focus of their rage. "I was used to treating people who had little hope and then saving their lives... But, with AIDS in those days, I saved no one. It was the darkest time of my life." Fauci told The New Yorker.

Fauci led the charge to get new antiviral drugs on the market and to change how clinical trials were run. He pushed for a program called Parallel Track, "which made unapproved AIDS drugs available as soon as they were demonstrated to be safe, even as clinical trials were continuing," reported The New Yorker. He was also a leading architect of the President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) a massive global initiative that began in 2003 to crush the disease and prevent infections (via CDC). "Because of the drugs that we developed in my institute," he told Holy Cross Magazine, "HIV has gone from being a complete death sentence to people living essentially normal lives with one pill a day."

He drove the development of biodefense drugs after 9/11

Even before the attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001, scientists at the NIAID, CDC, the Department of Defense, and other agencies were studying the threat, Fauci told Oncology Times. The anthrax attack in that same year, though very frightening to the nation, was small-scale. "The biological impact was trivial — more people died of influenza during that period — compared with the psychological impact," Fauci explained.

But when the White House called to put together a program to address the potential threat, Fauci's team at the NIAID got right to work. They looked at things they knew "the Soviet Union had been working on during the Cold War: anthrax, smallpox, Ebola, and other weaponized microbes" so they could come up with "therapeutics and vaccines" against them, he told Weill Cornell Medicine Magazine.

According to the NIAID website, the agency's focus is the development of broad-spectrum antibiotics and antivirals, as well as creating "multi-platform technologies that potentially could be used to more efficiently develop vaccines." Nevertheless, the physician isn't too worried about bioterrorism, as he thinks that releasing a pathogen on a population "isn't the easiest thing in the world to do" (via CBS News). He is optimistic about our future and offered reassurance, saying "All of the technology of science now arms us very well. The only trouble is, we have to keep up and we have to keep going."

His work ethic is strong

You know that old commercial for the Energizer bunny? The one where the bunny's beating a drum and keeps on going and going? Well, that's Anthony Fauci. He just doesn't know the meaning of "slacker." His drive, energy, and focus have carried him through grueling hours of research, meetings, and patient care at the NIAID for decades. Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, the immunologist was putting in some 18-hour days on other epidemics, including HIV/AIDS and Ebola.

Although Fauci told HuffPost "each day is different," he provided details about his Thanksgiving eve 2020 schedule. The day started at dawn and ended at about 7 p.m at the office. He often spends his workdays diving into hundreds of emails, texts, and phone calls, appearing on multiple news outlets, and video conferencing with heads of multiple agencies. Once he gets home, he takes a long walk with his wife, eats dinner, and then is back at the emails until his eyes give out around 11 p.m. or midnight.

He described COVID-19 as a "historic pandemic, the likes of which we haven't seen ... since 1918," he told The Washington Diplomat. "So getting worn out, getting burned out, getting too tired to go any further is not an option. It's just not in the cards."

He's a former marathoner

From a youth playing baseball, football, and basketball, to his working years as an avid runner, Dr. Anthony Fauci has always loved sports. The former marathon runner told The Wall Street Journal that his personal best time was at the Marine Corps Marathon in 1984: 3 hours and 37 minutes.

Despite his work schedule of 15-plus hour days as director of the NIAID and the challenges of tackling global infectious diseases, Fauci would carve out an hour at lunch most days for 5- to 7-mile runs around the Bethesda, Maryland, campus. "Mostly, I think the benefit [to running] for me is as a stress-reliever," he told the National Institute on Aging in a 2016 interview. "I have a pretty high-stress job ... so getting outside in the day and hearing the birds and smelling the grass is kind of a very pleasing thing for me."

Fast forward to present day, and the octogenarian has slowed his regimen just a bit. "I don't run very much anymore because at the end of the run, various parts of my body hurt so much," he told InStyle in 2020. These days, his preferred form of daily exercise is a 3.5-mile power walk with his wife, Christine.

He helped treat an Ebola patient

Ebola is one of those diseases that terrify the masses. Highly contagious and often fatal, it is spread through bodily fluids and by touching surfaces that have been contaminated. Symptoms start out like the flu but then the disease leads to blood-clotting problems. In late stages, bleeding from the eyes and other orifices can occur (via Johns Hopkins Medicine).

From 2014 to 2016, a rapidly spreading outbreak occurred, centered in the West African countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia (via World Vision). More than 28,000 people became infected, and, by the end, 11,000 of them lost their lives. In the U.S., two American nurses in Dallas, Texas, contracted the disease while caring for an Ebola-infected Liberian national, who later died. However, the nurses survived. One of them, Nina Pham, had been sent to the NIH facility in Bethesda, Maryland, where Dr. Anthony Fauci, in head-to-toe PPE gear, set aside two hours on most days to be personally involved in her treatment, along with a team of other specialists (via Science). She was later declared virus-free in a press conference, The Washington Post reported.

Fauci told Science magazine, "I now have a much, much more profound respect for the seriousness of this illness in some patients," he said. Since that outbreak, the FDA has approved an Ebola vaccine, which provides protection from the most virulent strain.

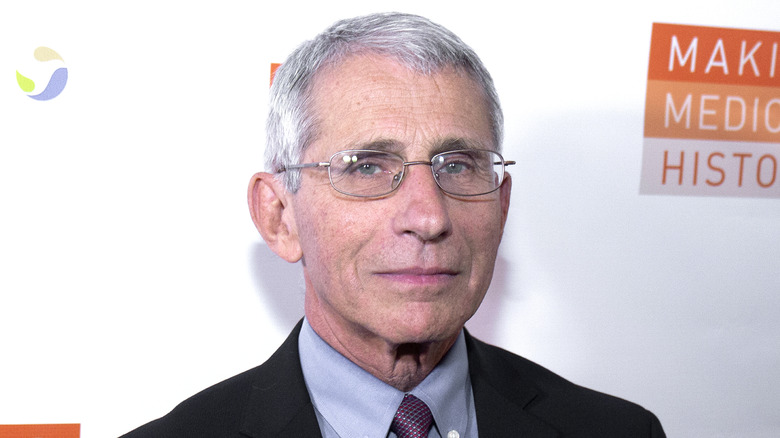

He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Medal of Freedom is the "highest civil honor a president can bestow," and in 2008 Dr. Fauci received that honor from President George W. Bush (via White House). The president's speech, according to a White House press release, was filled with praise and a few good-natured jokes.

He said, "As a physician, medical researcher, author, and public servant, Dr. Anthony Fauci has dedicated his life to expanding the horizons of human knowledge and making progress toward groundbreaking cures for diseases. His efforts to advance our understanding and treatment of HIV/AIDS have brought hope and healing to tens of millions in both developed and developing nations." The then-president went on to reveal a string of fun facts about the doctor. "Sometimes he forgets to stop working," he said. Bush also highlighted the doctor's long workweeks, adding, "And from time to time, he's even found notes on his windshield left by coworkers that say things like, 'Go home. You're making me feel guilty!'"

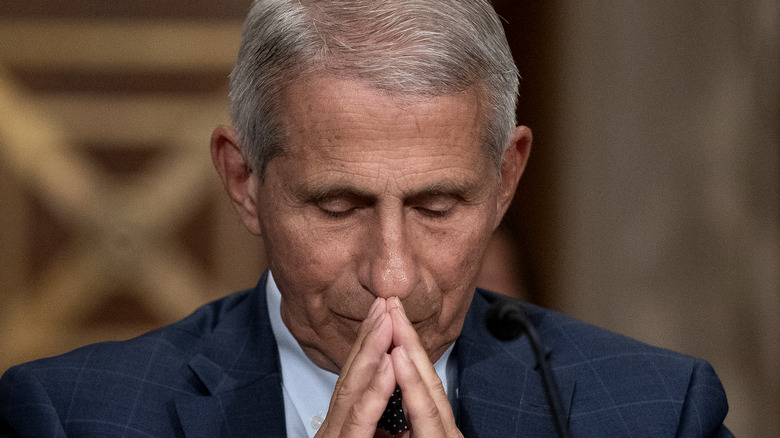

America's doctor isn't going to let criticism stop him

Four years before COVID-19, Dr. Fauci shared with "60 Minutes" what kept him up at night, saying, "An influenza-like respiratory-borne virus that's easily transmittable to which the population of the world has very little if any immunity against and that has a high degree of morbidity and mortality." Skip ahead to 2020, and a new virus was quickly spreading across the world.

Even with his five decades as a top infectious disease expert, most Americans had probably never heard of Dr. Fauci — not until he was thrust onto our TV screens and Twitter accounts daily, appearing in interviews and press briefings. He was the guy, America's doctor, the one who has a knack for breaking down the data and facts of COVID-19, in a way that's not too jargon-y. While most praised his efforts during the pandemic, Fauci has faced his critics. The backlash included not only verbal attacks but death threats, too, revealed WebMD. Federal agents began accompanying him for his safety (via CBS News).

Nevertheless, Fauci is determined to let science and data keep doing the talking. "One of the things I learned the first time I ever briefed a president, President Ronald Reagan, is that you have to make a decision when you're speaking truth to power that you should not be concerned about wanting to be liked," Fauci told Holy Cross Magazine. "Because once you start entering that into your equation, you might, subconsciously, slip into the situation where you tell somebody what you think they want to hear. And that is not truth."

Brad Pitt portrayed Dr. Fauci on SNL

Academy Award-winning actor Brad Pitt heeded the call at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic to play immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci in a "cold open" segment on the late-night comedy show Saturday Night Live. His three-minute portrayal of the bespectacled director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) — complete with gravelly New York accent and quick-witted remarks — earned Pitt critical acclaim and an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series (per USA Today).

Dr. Fauci, who is a longtime admirer of the actor and a good sport, says he enjoyed the performance. Ironically, he was also the likely catalyst for Pitt's casting in the role. "I think he did great," Dr. Fauci told Telemundo's "Un Nuevo Dia" (via CNN). "I mean, I'm a great fan of Brad Pitt, and that's the reason why when people ask me who'd I like to play me I mention Brad Pitt because he's one of my favorite actors. I think he did a great job."

How much is Dr. Fauci worth?

For his half-century of service in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Fauci earns an annual salary of $456,028 in the top spot as director, making him the highest-paid federal government employee as of this writing, as reported by the watchdog group Open The Books. Though salaries of federal employees are typically capped at Level IV of the Executive Schedule, per Forbes, exceptions are built into the system to be competitive with private-sector salaries for doctors and scientists. Dr. Fauci holds a medical degree from Cornell University.

According to a 2019-2020 public financial disclosure, the Fauci household's net worth is over $10.4 million. The 178-page official report goes into detail about the investments of Dr. Fauci and his wife, Christine Grady, who is the chief bioethicist at the NIH. It shows they hold a mix of stocks, bonds, and money market accounts, in addition to their combined salary of $668,312. Dr. Fauci further received $100,000 during both years of the disclosure for his work as the editor of a medical textbook. He also earned around $13,000 in travel reimbursements for personal appearances he made at various virtual galas and awards events.

Dr. Fauci is working on a memoir

Dr. Fauci will not be lacking for material when he writes his memoir. Having spent five decades at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the last 38 years of them in the top spot as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), you could say he has been through a lot. Dr. Fauci has overseen the country's response to domestic and global health threats such as HIV/AIDS, anthrax attacks, Ebola, COVID-19, and monkeypox. He has served under every president since Ronald Reagan, and as chief medical advisor to two presidents. The doctor is also the recipient of many prestigious awards, including the nation's highest civil honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

At the age of 82 in December 2022, Dr. Fauci will move on from his post at the NIH, he announced in a statement, and one of his projects will be writing about his life and career (via The New York Times). Though the doctor hasn't said what exactly will be in the book, it's expected that it will trace the pivotal moments of his life, from his Brooklyn upbringing and education in Jesuit schools, to his long tenure in public service, The New York Times reports. In the meantime, you can stream the National Geographic documentary "Fauci," released in 2021, which gives a behind-the-scenes look at his personal life and career, and the highs and lows as he navigated through the HIV/AIDS crisis and current COVID-19 pandemic.

He plans to keep working after his retirement

Known for his marathon workdays that sometimes reach up to 18 hours a day, it's not likely that Dr. Anthony Fauci will put his feet up anytime soon. The nation's top infectious-disease expert has broad goals after he leaves his high-profile position in December 2022 as the president's chief medical advisor and the top spot at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Foremost among those plans is writing a memoir and mentoring a new generation of up-and-coming scientists, he told NPR.

As the octogenarian maps out this next chapter — he doesn't call it retirement — he expects that his professional interests will continue to revolve around advancing science and public health. "After more than 50 years of government service, I plan to pursue the next phase of my career while I still have so much energy and passion for my field," he said in a National Institutes of Health news release. "I love everything about this place. ... [But] I don't want to be here so long that I get to the point where I lose a step," he told The Washington Post.