Strange Things People Really Used To Believe About Medicine

From ancient sleep temples to modern drug therapy, the practice of medicine has continued to advance and evolve over many centuries. Before the age of science, folk medicine regarded common maladies like the cold as an unavoidable part of existence, whereas more serious and debilitating diseases were often seen as having a spiritual, religious, or supernatural origin, such as a spell being cast or demonic possession (via Britannica).

There's evidence to suggest that prehistoric and early humans used mostly herbs, plants, fungi, and other natural products to treat and alleviate illnesses (via Discover Magazine). Some of these healing methods are still embraced in numerous cultures around the world today, often passed down through the generations (via Duke University). Some of the oldest texts on traditional medicine can be traced back to 2100 BCE in Ancient Mesopotamia, namely modern-day Middle East, which cite the use of prayer, sorcery, and medicinal plants alongside more conventional practices like the washing and bandaging of wounds (via National Center for Farmworker Health).

Here are some strange, intriguing, and downright bizarre ways that people have tried to cure diseases and rid themselves of various ailments over the course of medical history.

Centuries ago, medical treatments included everything from animal dung to moldy bread

The Ancient Egyptians left behind many relics that have shaped the modern world we live in today, an important one being the Ebers Papyrus (via Science Encyclopedia). Discovered in 1872, the papyrus is one of the oldest-known medical texts dating to circa 1550 B.C., which is speculated to have been created by a physician, based on some research, since the text alludes to "physician secrets." Documents of the time described treatments that were used for myriad diseases, illnesses, and injuries — ranging from familiar ingredients like honey to unconventional solutions like dog or donkey poop (via History).

Alongside the use of animal dung, the medical text unearthed in 1872 made reference to the benefits of moldy bread, which was applied topically to treat purulent wounds, rashes, and ulcers, reports a 2016 review article published in the Journal of the German Society of Dermatology. Moldy bread can be regarded as one the earliest forms of penicillin — the most widely-used antibiotic to date — and has been lauded for its potent wound-healing and anti-bacterial properties for centuries in cultures across China, Serbia, Greece, and Rome. "Phycomyces blakesleeanus" is the specific kind of fungus that can be found on stale bread as well as other organic compounds like feces, and dead wood, which gives it its medicinal prowess (via New Scientist).

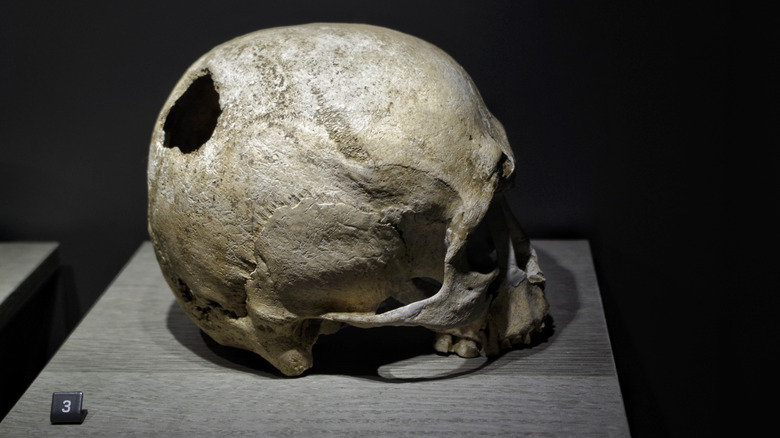

A hole in the skull was used to treat a variety of conditions

When it came to healing physical and mental ailments, our ancestors seemed to believe there was nothing quite as effective as a hole in the ol' head. Trepanning, also known as trepanation, was a curious surgical procedure that involved drilling an opening into the skull (via Medical News Today).

Various cultures practiced trepanation in some form, explained Medical News Today. Prehistoric skulls with evidence of trepanning were discovered as early as the Mesolithic period, emerging in North Africa, Ukraine, and Portugal. Its benefits were alluded to in the "Hippocratic Corpus," a collection of early Ancient Greek medical texts (via Academic Medicine). It's likely that the Incas discovered trepanation by accident and quickly realized its purported medical potential, anthropologist John Verano told National Geographic.

A wide spectrum of theories can be found on the motivations behind trepanation. A 2011 case study states that it was used to treat headaches, epilepsy, tumors, physical injuries, and mental health issues. It was also attributed to initiations (i.e., a right of passage into warrior status) and religious and supernatural reasons. Nevertheless, the procedure fell out of favor with the medical community in the 19th century. Doctors sometimes still drill holes into patients' skulls today — known as craniotomy — to treat life-threatening conditions like brain lesions, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

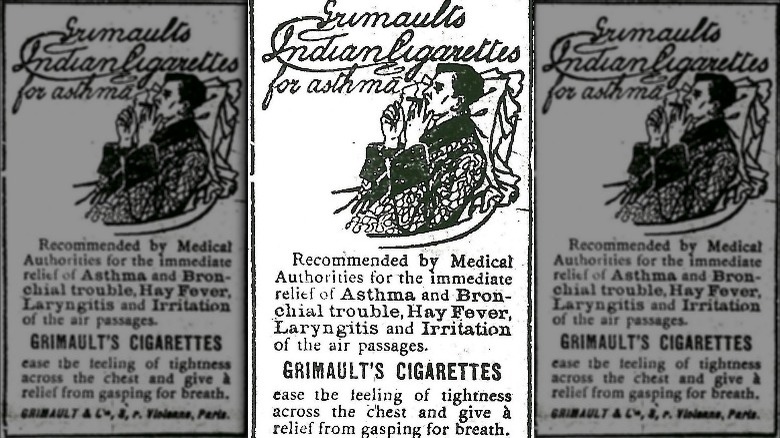

Cigarettes were prescribed for lung problems

Smoking and asthma are a pretty toxic combination. Whether it's firsthand or secondhand, smoke inhalation deprives the lungs of oxygen and can be a major trigger for respiratory problems. But shockingly, cigarettes were once prescribed by doctors as a remedy for asthma (via Snopes).

Page's Inhalers are one example of medicated cigarettes that came to rise in the early 20th century, containing stramonium leaves and other ingredients such as tea leaves, chestnut leaves, gum benzoin, and kola nuts, as reported by Pharmacy Times. They were designed to provide "temporary relief of paroxysms of asthma ... hay fever, and simple nasal irritations," explained the Soderlund Drugstore Museum. Inhaling smoke from burning plants and herbal mixtures through a pipe was advocated for treating asthma, coughs, and a variety of other respiratory conditions, by Greek, Roman, and Indian physicians, explains a research article in the journal Medical History.

Many doctors smoked during the 1930s and '40s. And in the early 1950s, tobacco executives developed ad campaigns featuring images of physicians posing with a cigarette to showcase their favorite brand. Some companies even went as far as claiming that their cigarettes could soothe smokers' throats and protect against irritation, alongside quotes by physicians. In 1957, a scientific report revealed that cigarettes contain hundreds of cancer-causing carcinogens. It wasn't until the research evidence for the dangers of smoking started to appear in national magazines like Time and Reader's Digest that tobacco executives began to rethink and readjust their marketing strategies.

Tobacco enemas were a popular medical practice

The practice of blowing tobacco smoke up the rectum through a tube was first used by Native American tribes to treat various illnesses (via BC Medical Journal). Inspired by this unique holistic technique, two English doctors, William Hawes and Thomas Cogan, advocated for its use in reviving people who had almost drowned. The tobacco smoke was mistakenly believed to warm up the body and stimulate respiration. Eventually, the equipment used for this procedure, namely "resuscitation kits," were kept alongside major waterways in the UK, such as The Thames (via The Lancet).

At around the same time, tobacco was imported to England from Virginia to be chewed and smoked in a clay pipe (via BC Medical Journal). By the late 18th century, tobacco smoke enemas were prescribed by medical practitioners in Europe to treat a wide range of conditions from colds to cholera to typhoid fever and stomach cramps.

Their use in Western medicine started to decline in 1811 when English scientist Ben Brodie determined that nicotine was harmful to the heart, per BC Medical Journal. Not long after, this unusual practice lost its popularity among doctors. It was no longer administered for illnesses or used as a resuscitation method in near-drownings, but tobacco enema kits could still be purchased in secondhand stores in London.

Gladiator blood was used to treat epilepsy

The Romans believed that drinking the blood of fallen gladiators (or eating their liver) was a panacea for epilepsy (via Medpage Today). Many ancient Roman authors wrote about this bizarre rite starting in the first century, the origins of which were said to lie in Etruscan funeral rituals, according to a research article published in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. The idea was that people could absorb the strength and vitality of these young, healthy men through consuming their blood, which purportedly had medicinal and magical properties (via Smithsonian Magazine).

"If you could harness that energy right at the point of death, you could ingest some of this healthfulness," Lydia Kang, author and doctor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, told Medpage Today. "In other words: you are what you eat." Because seizures are episodic, spontaneous recovery of some epileptics contributed to the illusion that this treatment worked, Kang added. While the influence of this ancient cannibalistic practice diminished over the course of ancient Roman times, the therapeutic use of slain gladiators' blood continued for centuries, noted a study published in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences.

Schizophrenia was treated with insulin coma therapy

Insulin coma therapy (also known as insulin shock therapy) became the frontline treatment for schizophrenia between the 1930s and 1960s, as a report in the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences highlighted. It was considered a potential bridge between psychiatry and mainstream medicine, a decade after insulin was recognized as a "miracle drug" for treating diabetes. Based on a 1960 research article published in The American Journal of Nursing, placing a patient into a medically induced coma was seen as an effective treatment for numerous mental health issues including anxiety, depression, hallucinations, obsessive and compulsive thinking, and more.

The "treatment" was developed by a neurologist called Manfred Sakel in 1927, who administered low doses of insulin to treat addiction and psychopathology (via Science Museum). After one of his patients slipped into a coma-like state and emerged feeling mentally better, Sakel hypothesized that an insulin coma could provide therapeutic relief to people with schizophrenia. The treatment involved increasing the dosage of insulin each day over several weeks or months until the patient lapsed into a coma (via JSTOR Daily). The insulin could then be tapered down gradually — a process that was repeated up to 30 and 50 times.

The therapy fell out of fashion in the 1960s alongside the emergence of antipsychotics, per JSTOR Daily. Many doctors discredited its efficacy soon after, but there were still some practitioners that clung to the idea that insulin-enduced deep sleep could help restore an individual's mental health.

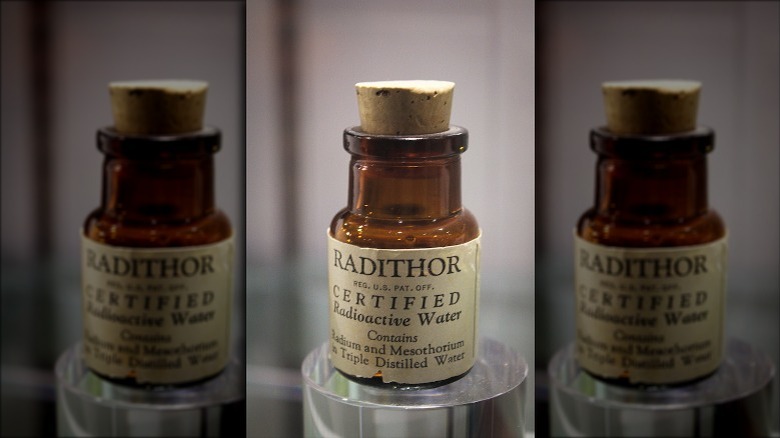

Radioactive drinks were sold for their purported healing properties

The early 20th century saw the rather unusual rise of radioactive beverages. Far from being just a wild new craze, they were deemed a legitimate treatment by the medical community and were thought to cure just about everything from impotence to arthritis to mental illness (via National Geographic). Early research even claimed that radium — the beverage's highly radioactive main ingredient — could prevent aging due to its ability to stimulate cell activity.

As the popularity of these drinks continued to soar, radium gradually made its way into various products including dressings and chocolates, promising to increase vigor and provide consumers with a number of health benefits (via Stanford University). People visited radium spas to soak in irradiated water and inhale radon straight into their lungs (via American Nuclear Society). One of the most mainstream radium-boasting products was Radithor, an all-natural radon water, which was said to boost energy, with one scientific paper claiming that it could increase "the sexual passion of water newts" (via The Conversation). But unsurprisingly, Radithor failed to deliver, causing bone damage instead.

In 1914, Ernst Zueblin, a medical professor at the University of Maryland, published a scientific review that showed that bone necrosis and ulcerations were a common side effect of radium consumption (via CNN). By the 1930s, scientists understood that exposure to radiation can damage cellular DNA and cause cancer (via National Geographic).

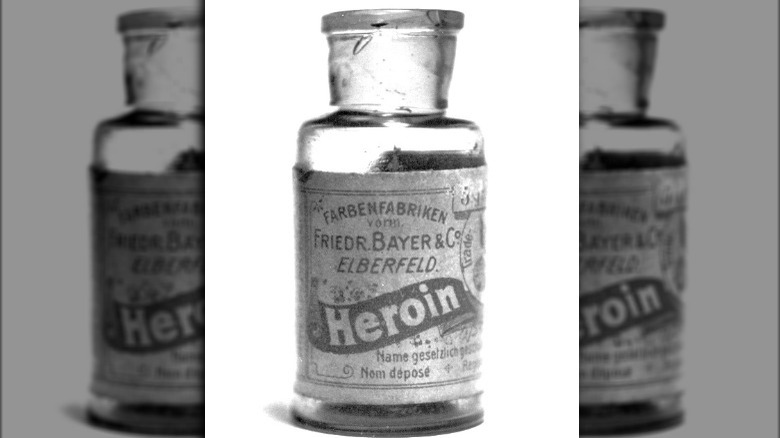

Heroin was prescribed for various ailments

The very first batch of heroin was concocted by an English chemist named C.R. Alder Wright in 1874. It was borne out of an attempt to create a non-addictive version of morphine (via The Harvard Gazette). But things didn't quite go as planned. Instead, heroin — also made out of the opium poppy plant — turned out to be far more potent than its predecessor.

From the initial clinical trials, the substance was quickly regarded as a "wonder drug" and was added to the recipes of cough syrups as a cough suppressant, detailed CNN. By the late 19th century, the German pharmaceutical manufacturer Bayer sold a cough syrup under the brand name "Heroin," marketing it as a safer substitute to morphine (via Yale School of Medicine).

In 1898, Bayer also began producing heroin-laced aspirin, which was specifically marketed towards children as a balm for sore throats, colds, and coughs (via History). The bottles even pictured children happily taking the medicine alongside their parents handing them a spoon. But physicians and pharmacists soon realized that users were becoming heavily dependent on these products. And in 1924, heroin became illegal (via CNN). Since its introduction in the 19th century, it's continued to cause serious and widespread health and social problems across the globe.

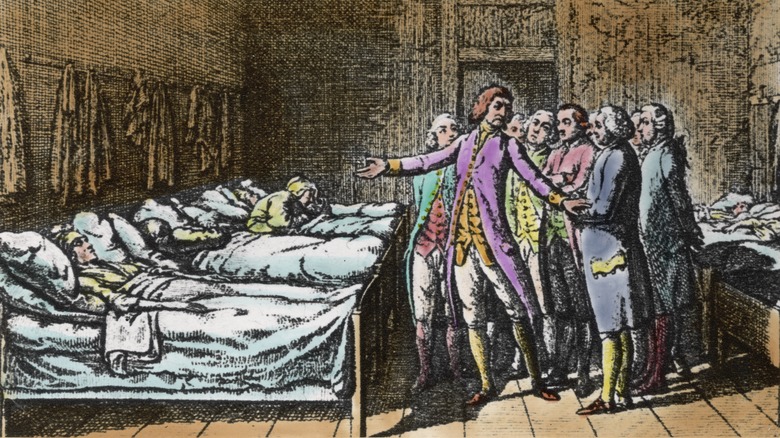

Bloodletting was used to rid the body of impurities

Bloodletting — namely withdrawing blood from the veins for therapeutic purposes — is an ancient practice (via BC Medical Journal). "The practice of bloodletting began around 3000 years ago with the Egyptians, then continued with the Greeks and Romans, the Arabs and Asians, then spread through Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance," the journal revealed. The gruesome procedure involved cutting a vein or artery, usually at the elbow or knee, in order to extract blood from the body in a controlled way until the patient passed out (via Healthline). Physicians used various specialized instruments and techniques ranging from scalpels to lancets to leeches.

The efficacy of bloodletting relied on the premise that the procedure could rid the body of certain impurities as a way to treat a host of diseases and conditions, per Healthline. Around the 5th century B.C., the Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates claimed that physical and mental illnesses stemmed from an imbalance in the four humors in the body — black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood — which could be corrected via bloodletting (via BC Medical Journal).

Around the 1600s, physicians began to question the science behind bloodletting, with a number of research studies demonstrating its inefficacy in the late 1800s, explained Healthline. Shortly after reaching its height in the 19th century, its legitimacy was discredited and the therapy started to decline in popularity. Today, it's seldom used in Western medicine bar a few select medical cases.

Medical vibrators were devised to treat 'female hysteria'

The invention of the vibrator in the 19th century had little to do with women's pleasure. Instead, it had much more to do with their supposed emotional instability and fragility (via The Atlantic). Physicians in the Victorian era used steam-operated vibrators to treat "female hysteria" — a now-defunct diagnosis that covered various issues from anxiety to sleeplessness to nervousness (via Psychology Today). In 1869, American physician George Taylor patented the first electromechanical medical vibrator called the "Manipulator" to assist doctors in treating patients, while physician Mortimer Granville invented the first portable, battery-powered device in the early 1880s (via The New York Times).

For centuries, people subscribed to the belief that women were biologically weak, revealed a report published in the Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. In the ancient medical world, doctors based their theory of hysteria on the idea that a woman's womb wandered around her body, triggering a host of disorders by interacting with other organs like the brain, lungs, and liver. Many believed that pelvic massages involving clitoral stimulation could effectively reduce the myriad symptoms of hysteria and provide therapeutic benefits (via The Embryo Project Encyclopedia).

In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association finally removed the once-recognized term "hysteria" from the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In the 1960s, the vibrator was no longer being sold as a medical instrument but rather was marketed as a sex aid for women to purchase for themselves, thanks to its ability to produce orgasms, per The New York Times.

A lobotomy was considered a cure for mental illness

The lobotomy is often regarded as "one of the most barbaric treatments" for mental illness, reported Verywell Mind. It was established in the 1930s as part of a new wave of interventions for neurological illnesses, intended to solve the problems of overcrowding in mental institutions at a time when very few interventions were found to be effective.

Lobotomies were the treatment of choice for conditions such as schizophrenia, depression, panic disorder, and mania, explained a 2011 article published in the Journal of Neurosurgery. The procedure comprised a series of different operations that aimed to sever the brain's nerve fibers that connected the frontal lobe — the region responsible for thinking — to other areas of the brain (via Live Science). Neurologist Walter Freeman, who conducted the very first prefrontal lobotomy in the United States, felt that it was nearly as safe as "an operation to remove an infected tooth" (via Verywell Mind).

"The behaviors [doctors] were trying to fix, they thought, were set down in neurological connections," Barron Lerner, a medical historian and professor, told Live Science. "The idea was, if you could damage those connections, you could stop the bad behaviors." Performed for more than two decades, the lobotomy reached its height of popularity in the 1940s but eventually fell out of favor with the medical community in the late 1950s, details researchers. The controversial surgery was rarely performed by doctors as scientists turned to more ethical and effective interventions such antipsychotic and antidepressant medications (via Verywell Mind).

Mercury was prescribed to treat syphilis

Mercury is fairly well-known for its toxicity. Exposure to this neurotoxin can cause health issues including muscle weakness, vision loss, impaired hearing and speech, and lack of coordination of movement, explains the Environmental Protection Agency. But this silvery fluid metal was once touted as a healing elixir and topical ointment in ancient Persian, Greek, Indian, and Arabic cultures, according to researchers. Seen as medicinal rather than poisonous, it was used for a diverse range of diseases and ailments from melancholy to constipation to influenza (via Science Friday).

Calomel (mercurous chloride) became a commonly-used medicine between the 16th and early 20th centuries, per Science Friday. The Swiss physician and philosopher Paracelsus believed that calomel helped purge the body through large amounts of drooling, reaching its efficacy once three pints of saliva had been produced. The odorless white powder was believed to rid the body of harmful toxins, and it quickly became a medical solution for sexually transmitted diseases like syphilis in Protestant Europe (via The Pharmaceutical Journal). By the mid-20th century, scientists and physicians became aware of the damaging side effects of mercury, which often included lost teeth, decaying bones, neurological problems, and death (via Science Friday).

Arsenic was used to treat various diseases

Arsenic is considered one of the oldest medicines in history, also referred to as the "king of poisons", explains a 2014 article in the International Journal of Epidemiology. The use of arsenic featured in various cultures including ancient Greek and Roman civilizations as well as traditional Chinese medicine, says researchers.

Notorious for its toxic properties, arsenic was utilized by the Romans as a weapon against their enemies. And for centuries it even became the poison of choice for women who wanted to kill their husbands (via Ranker). Unsurprisingly, this led to the House of Lords in England trying to pass a law that made it illegal for women to purchase arsenicals in 1851, revealed The New Yorker. Despite being recognized as a poison, the chemical was also marketed as a beauty product during the Victorian era for women to lighten their skin (via National Geographic).

Before the introduction of penicillin in the early 1940s, the deadly substance was unexpectedly used for less sinister purposes including the treatment of diseases such as syphilis and trypanosomiasis (aka "sleeping sickness"), and less commonly for malaria and tuberculosis, according to the Journal of Military and Veterans' Health. Arsenic compounds were added to a vast array of medicinal tinctures, balsams, and tablets. This "miracle drug" is still available in medicine today as a treatment for specific subtypes of leukemia and trypanosomiasis.

The spinning chair was a mental health intervention

The spinning chair, also known as "rotational therapy," was once all the rage, according to research published in Frontiers in Psychiatry. It became somewhat of a health trend around the mid-19th century. This creative practice was pretty self-explanatory: Patients were spun in a specially constructed whirling chair until they entered into a state of vertigo, vomiting, and unconsciousness, says a 2005 scientific article.

The therapy was introduced by Charles Darwin's grandfather Erasmus who hypothesized that the "excessive spinning" could alleviate mental health issues like schizophrenia and hysteria, as the increased pressure would reduce "brain congestion" (via Medscape). This was subsequently developed into a novel psychological treatment by a doctor named Joseph Mason Cox, who used a specially designed chair to rotate patients' bodies until they reached a state of calmness and tranquility, explained researchers.

Variations on Cox's chair were widely used in Europe throughout the 19th century, with several doctors espousing the therapeutic benefits of spinning for patients with mania as well as aiding sleep. The treatment eventually ceased to exist, as the scientific evidence for it continued to be called into question.

Bladder stone patients were treated by lithotomy

Lithotomy began with ancient Greek surgeons in the days of Homer, and lasted until the middle of the 18th century, as explained in a Urologia Internationalis report. The ancient art involved the opening of the bladder via the perineum in order to remove "calculi," namely stones from the bladder or urinary tract. An incision was first made on the patient's perineum. Then, "two fingers of the surgeon's left hand were introduced into the patient's rectum while an assistant pressed on the lower abdomen to encourage descent of the stone near the neck of the bladder," the report explained. The stone was then pulled through the wound. As if that wasn't enough to make you queasy — the procedure most likely took place without the use of anesthesia (via International Museum of Surgical Science).

The technique of lithotomy dates back to the 1st century when it was first mentioned by a Roman physician named Cornelius Celsus (via the International Museum of Surgical Science). But descriptions of it can also be found in ancient Egyptian, Hindu, and Greek Writings, according to The Royal Society of Medicine. Evidently, the procedure was an agonizing process that often had dire consequences for patients including infections, long-lasting damage to the rectum, and permanent incontinence, per the International Museum of Surgical Science. The practice of open lithotomy eventually went out of vogue, as it was replaced by minimally invasive methods.