How Your Gut Bacteria Could Restore Your Immune System

New research about the microorganisms that live in our gut could lead to new treatments for conditions related to the immune system. In a study published this month in the journal Nature, researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City said they studied thousands of patients being monitored during their recovery from chemotherapy and stem-cell engraftment.

The aggressive treatment causes large shifts in both circulatory immune cells and microbiota, which enabled researchers to study a suspected relationship between the two. "The scientific community had already accepted the idea that the gut microbiota was important for the health of the human immune system, but the data they used to make that assumption came from animal studies," systems biologist and study co-author Joao Xavier told Medical News Today.

To better understand the significance of their research, it helps to know how the body reacts after undergoing treatment for certain cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma. Following chemotherapy and radiation therapy, a patient must receive an injection of bone marrow or stem cells from a donor's blood, because the cancer treatment also kills healthy immune cells. The bone marrow or stem cells help restore the patient's ability to make their own blood cells.

Boosting "friendly" bacteria in the gut can speed up the immune system's recovery

Recovering patients also must take antibiotics within the first few weeks of receiving stem cells or bone marrow because they are still vulnerable to infections. To protect the patient, these antibiotics don't differentiate between the "friendly" bacteria in the digestive system and anything that's harmful there; they kill everything. A patient can stop taking antibiotics once their immune system is stronger, of course, allowing the digestive system and its delicate balance of microorganisms to recover.

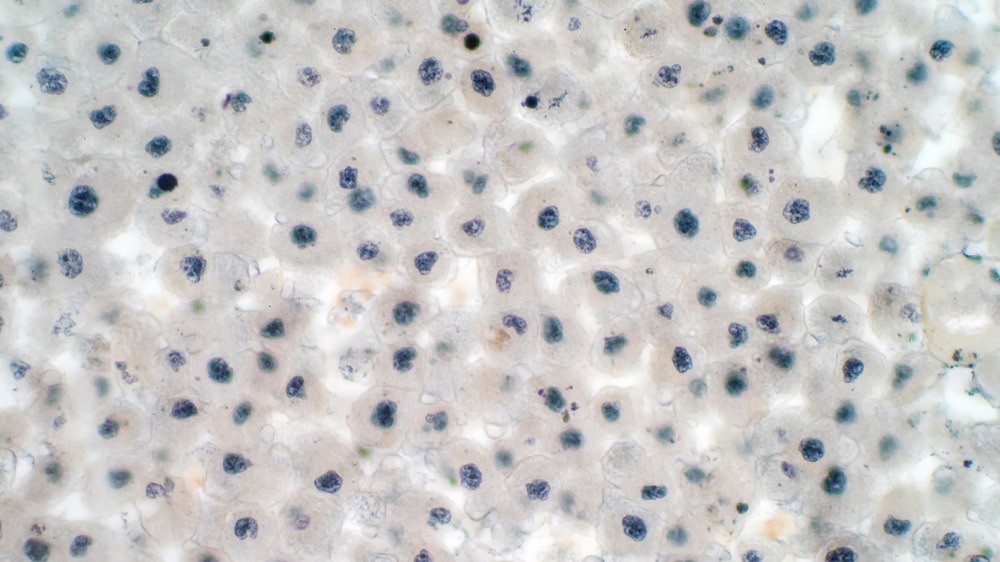

Using blood and fecal samples, the researchers tracked daily changes in the immune cells in the blood and gut microbiota in more than 2,000 patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center from 2003 to 2019. They also used a machine-learning algorithm to identify patterns in the data, which also included information about the patients' medications and side effects.

Through computer simulations, the researchers predicted that by enriching microbiota with three "friendly" types of gut bacteria would speed up the recovery of the patients' immune systems. The research could eventually suggest ways to make cancer treatments safer by more closely regulating the microbiota, co-author Marcel van den Brink told Medical News Today.