Details About Acetaminophen You Never Expected

Chances are you have acetaminophen, like Tylenol, hanging out in your medicine cabinet. It's many people's go-to choice for reducing a fever or relieving headaches and other minor aches and pains. In fact, according to the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, 23 percent of American adults take acetaminophen in any given week. It's cheap, effective, and generally regarded as safe, which is why it's considered an "essential medicine" by the World Health Organization.

While you may not think twice about popping some Tylenol when your temperature starts to rise or your head starts to throb, it's important to make sure you're not overdoing it. Experts generally recommend adults take no more than 4,000 mg of acetaminophen per day. That's equivalent to eight extra-strength (500 mg) tablets. However, some people may be more sensitive to the drug, so it's best to take only as much as you need and not to exceed 3,000 mg if possible.

Acetaminophen may seem like a simple, harmless medication, but there's a lot more history and controversy to these little pills than you might expect.

Acetaminophen is in more medications than you think

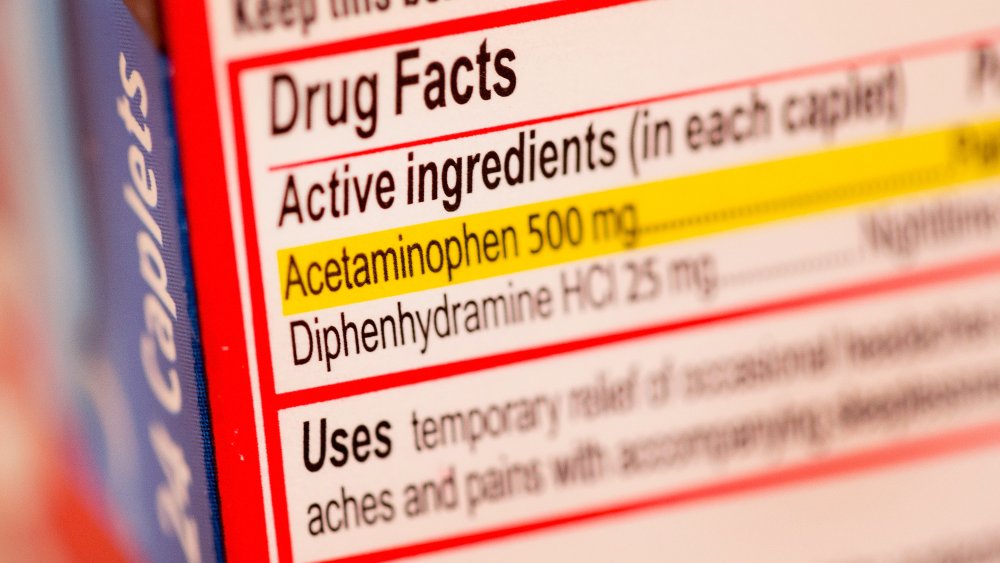

The tricky thing about acetaminophen is that it can be surprisingly easy to accidentally take more than the recommended maximum daily dose of 4,000 mg. That's because it's in more products than just Tylenol. In fact, the National Center for Health Research noted that more than 600 medications contain acetaminophen; it is reportedly the most common drug ingredient in America. These drugs can come in the form of tablets, capsules, syrups, or drops and often include other active ingredients. If you're trying to treat multiple issues at the same time — say, menstrual cramps and a head cold — you may be doubling or tripling up on acetaminophen without even realizing.

To make things even trickier, acetaminophen may be listed as something else on the medication's label. Check for names like APAP, N-acetyl-para-aminophenol, acet, acetamin, acetaminoph, and paracetamol as they all indicate acetaminophen.

According to Medline Plus, acetaminophen is often found in cold and flu remedies, allergy medications, and drugs marketed to treat a specific type of ache, such as menstrual cramps, migraines, or back pain. Ingredients commonly used alongside acetaminophen include aspirin, caffeine, phenylephrine, phenyltoloxamine, dextromethorphan, guaifenesin, and pseudoephedrine. Prescription medications containing acetaminophen often also include opioids such as hydrocodone and oxycodone.

Acetaminophen was developed from coal tar

It may be hard to believe, but acetaminophen was developed from coal tar, a byproduct of coal processing. In the 1800s, coal tar was used to create a number of medications to treat pain and fevers. In 1893, German physiologist Joseph von Mering discovered N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethanamide, later renamed paracetamol, while searching for a safer alternative to another drug derived from coal tar. This new drug, however, appeared to have serious side effects, so it was abandoned for many years. It's now believed that those side effects were actually caused by an impurity, not the drug itself.

Decades later, in 1947, Yale physiologists David Lester and Leon Greenberg revisited the abandoned drug and determined how it was metabolized in the body. In the early 1950s, amid growing concern about aspirin's GI side effects, interest in acetaminophen skyrocketed. By the middle of the decade, acetaminophen was appearing in prescription medications and, in 1961, Philadelphia-based McNeil Laboratories released the first over-the-counter acetaminophen products under the brand name Tylenol.

As of this writing, a coal tar derivative is still used to make acetaminophen. It can also be found in some shampoos and topical treatments for psoriasis. Although generally considered safe, coal tar has been linked to certain cancers.

We don't actually know for sure how acetaminophen works

Acetaminophen gets the job done when it comes to reducing fever and easing pain, but scientists don't fully understand exactly how it does these things. An article in Chemical & Engineering News explained, "Researchers have been guessing at acetaminophen's mechanism of action for decades. Some explanations involve chemical messengers of inflammation and pain. Others invoke aspects of neurotransmission in the brain and spinal cord."

One theory is that acetaminophen blocks cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are needed to create prostaglandins. Prostaglandins are molecules that help communicate pain and inflammation throughout the body. NSAIDs such as ibuprofen also block COX enzymes, but researchers believe acetaminophen targets a different part of the COX enzyme than NSAIDs do.

Another theory is that acetaminophen activates a specific neural pathway in the spinal cord that also produces the sensations of pain or itchiness in response to capsaicin (the active ingredient in spicy peppers). It seems counterintuitive, but activating this pathway may actually dull other types of pain. A third possibility is that acetaminophen interacts with serotonin to relieve pain. We don't need to know why it works to reap acetaminophen's benefits, but finding an answer could lead to an even safer and more effective alternative.

Acetaminophen is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States

It's difficult to imagine that something as ubiquitous and unassuming as acetaminophen could be really dangerous, but it's true. Taking too much acetaminophen is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States, according to the Mayo Clinic. This can happen after taking either one very large dose or taking many higher than recommended doses over the course of a few days or weeks.

Acute liver failure is a medical emergency that may require a liver transplant and it can even be fatal. Symptoms include pain in the upper-right abdomen, abdominal swelling, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), nausea, and disorientation. If not promptly treated, it can lead to complications beyond the liver, like internal bleeding, infections, kidney failure, and fluid buildup in the brain.

How exactly does acetaminophen damage the liver? MedicineNet explained that as acetaminophen is metabolized, it creates a toxic compound known as NAPQI. The liver uses the antioxidant glutathione to remove NAPQI, but if there's too much NAPQI in the blood or there isn't enough glutathione to do the job, the liver becomes overwhelmed and can't get rid of the NAPQI fast enough.

Acetaminophen and alcohol are a bad combination

If Tylenol is currently your go-to hangover remedy, you may want to start looking elsewhere in your medicine cabinet. According to the Cleveland Clinic, both acetaminophen and alcohol are processed by the liver, which uses the antioxidant glutathione to remove the toxic byproducts of these substances.

Taking the recommended dose of Tylenol after a single night of drinking most likely won't be a problem, but frequent moderate or heavy drinking (more than one drink a day for women or two drinks a day for men) can deplete your liver's glutathione stores, making it ill-equipped to deal with a large dose of acetaminophen.

However, acetaminophen with even small amounts of alcohol could be bad news for your kidneys. A 2018 study published in Preventive Medicine Reports concluded, "Statistically significant increased odds of renal [kidney] dysfunction were noted among respondents who reported use of therapeutic doses of APAP [acetaminophen] and light-moderate amount of alcohol." The researchers defined "light-moderate" drinking as up to one drink a day for women and two drinks a day for men. Although the study's authors hypothesized that even doses of acetaminophen below the recommended 4,000-mg cap could cause kidney damage, they couldn't determine a threshold dose at which those ill effects started to appear.

There's an antidote for acetaminophen poisoning

An estimated 150 to 500 people die of an acetaminophen overdose or poisoning each year in the United states, and another 55,000 to 80,000 take a trip to the emergency room for the same reason. MedicineNet noted that approximately two-thirds of overdoses among adults are intentional. Among children, overdose usually occurs because parents don't realize they're giving their children too much acetaminophen.

Thankfully, there's an antidote that can prevent acute liver failure from an acetaminophen overdose. The supplement N-acetylcysteine (NAC), given either orally or intravenously, can reverse the toxic effects of acetaminophen. It does this in two ways. First, it acts as a glutathione replacement. The liver uses glutathione to help get rid of NAPQI, the toxic byproduct created when acetaminophen is metabolized. In the case of an overdose, the liver doesn't have enough glutathione to handle all the NAPQI. Second, NAC can directly bind to NAPQI, rendering it neutral. "If treatment of a toxic overdose is begun early," Healthline explained, "the person may recover with no long-term health problems."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Can acetaminophen have an effect on your blood pressure?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, high blood pressure (hypertension) affects 45 percent of American adults. It's a major risk factor for both heart disease and stroke.

A 2013 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology reviewed a number of studies and trials to see if acetaminophen affected blood pressure. The results, however, were mixed. The researchers noted, "Some, but not all, of the observational studies, which included over 147,000 patients, showed an increased risk of hypertension with paracetamol [acetaminophen] use." Three smaller randomized studies revealed a minor increase in systolic blood pressure of about 4 mmHg, two found no change, and one actually concluded that acetaminophen lowered blood pressure.

WebMD noted that, unlike NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen does not appear to increase an individual's risk for heart disease or stroke. So even if acetaminophen does cause a slight increase in blood pressure, it's likely no cause for concern.

Taking acetaminophen may lead to risky behavior

Does something as simple as popping a few Tylenol make you more likely to engage in unsafe activities like speeding or unprotected sex? The idea may sound a little out there, but a 2020 study published in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience suggests that it might. Researchers gave participants a 1,000-mg dose of acetaminophen and then had them complete several laboratory simulations and questionnaires. They found that acetaminophen reduced perceptions of risk and, as a result, increased risk-taking behavior during the experiments.

Dr. Baldwin Way, the study's co-author, explained to ScienceDaily, "Acetaminophen seems to make people feel less negative emotion when they consider risky activities — they just don't feel as scared."

In the study, participants' risky behavior was confined to computer simulations. In one experiment, participants clicked a button to inflate an on-screen balloon and earn virtual money. They could inflate the balloon as much as they wanted, but if it popped, they would lose the money they'd earned. "For those who are on acetaminophen, as the balloon gets bigger, we believe they have less anxiety and less negative emotion about how big the balloon is getting and the possibility of it bursting," Way revealed. While taking risks during a game is harmless, this devil-may-care attitude could be dangerous in the real world.

Taking acetaminophen while pregnant may present future risks

While acetaminophen is generally considered safe to take during pregnancy, some research has suggested that children born to moms who took the drug may be at greater risk for behavioral issues. One 2019 study found that taking acetaminophen between 18 and 32 weeks' gestation increased the likelihood of "conduct problems" when children were between the ages of 42 and 47 months.

The study authors noted, however, that "there were few associations with behavioral or neurocognitive outcomes after age 7‐8 years." In an interview with Healthline about the study, lead author Dr. Jean Golding noted that the results don't prove that acetaminophen causes the hyperactivity and attention difficulties that researchers observed, but "it makes the likelihood stronger."

A paper published in the American Journal of Epidemiology in 2018 attempted to determine if there was a link between taking acetaminophen while pregnant and ADHD or autism among children. While the researchers found that "acetaminophen use during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk for ADHD [attention deficit hyperactivity disorder], ASD [autism spectrum disorder], and hyperactivity symptoms," they cautioned that there are limitations to the study.

Acetaminophen can kill more than just your physical pain

Getting passed over for a big promotion or stood up on a date can feel just as unpleasant as stubbing a toe or hitting your head. The "pain of rejection" is a real thing. As the authors of a 2010 study published in the journal Psychological Science pointed out, both physical and social pain "may rely on some of the same behavioral and neural mechanisms." And when you use a drug like acetaminophen to dull physical pain, you also relieve feelings of psychological pain and rejection.

The study consisted of two experiments. In the first, participants took either acetaminophen or a placebo every day for three weeks and tracked how often they felt "social pain" during their day-to-day lives. Those who took the acetaminophen reported fewer instances of psychological distress. In the second experiment, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to measure the brain activity of participants. The researchers found that acetaminophen reduced activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula — brain regions associated with thinking about both social and physical pain.

Acetaminophen may make you less empathetic

Although Tylenol can relieve your pain, it may make you less concerned with other people's suffering, according to a 2016 study published in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. Researchers gave participants either 1,000 mg of liquid acetaminophen or a placebo and then tasked them with two experiments to gauge empathy. Those who'd received the acetaminophen ended up showing less concern for others.

The researchers speculated that this is because "empathizing with others' pain shares some common psychological computations with the processing of one's own pain." In other words, by dulling our own pain, acetaminophen makes our brains less able to conceptualize the pain other people might be experiencing.

The researchers also found that acetaminophen reduced participants' empathy when they thought about or witnessed someone experiencing psychological pain or social rejection. Because it's such a commonly used drug, the study authors speculated that acetaminophen could have negative impacts on our interpersonal relationships. In an interview with ScienceDaily, lead author Dr. Baldwin Way explained, "Empathy is important. If you are having an argument with your spouse and you just took acetaminophen, this research suggests you might be less understanding of what you did to hurt your spouse's feelings."

Acetaminophen can cause rare but serious skin reactions

Acetaminophen may produce serious, even life-threatening, skin reactions, according to the Food and Drug Administration. These include acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). These conditions can also be triggered by other medications. There's no way to predict who will develop one of these conditions — and just because you've taken acetaminophen for years doesn't mean you're immune.

AGEP is the mildest of the three conditions and leads to areas of red skin with dozens or even hundreds of pus-filled blisters. Individuals may also experience a fever and elevated white blood cell counts. The condition usually goes away within two weeks of stopping the offending medication. In the case of both SJS and TEN, flu-like symptoms are followed by a rash, blistering, and detachment of the epidermis (the topmost layer of skin). TEN is more severe than SJS, but both generally require hospitalization and may take weeks or months to recover from. Scarring, changes in skin coloration, blindness, internal organ damage, and even death may occur.

But before you throw out your Tylenol, it's important to note that these reactions are extremely rare. Between 1969 and 2012, there have only been 107 cases.

The FDA considered banning all acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is in so many products that it's hard to imagine a world without it, but the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) came close to removing it from American pharmacy shelves. In 2009, an FDA panel considered banning all acetaminophen because of its role as the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States. In the end, the panel voted to propose a ban only on two specific combination prescription products, Percocet (oxycodone and acetaminophen) and Vicodin (hydrocodone and acetaminophen).

Then, in 2011, the FDA put a dose restriction on prescription products containing acetaminophen, including opioid painkillers. Manufacturers were thus limited to no more than 325 mg of acetaminophen per tablet or capsule in any prescription product. These medications must also carry a warning box highlighting the risk of acute liver failure.

Over-the-counter acetaminophen was not affected by the FDA's rule and may contain higher dosages of acetaminophen per dose. However, such OTC products do contain a warning on the label and, in 2013, Tylenol added an additional acetaminophen warning on their product's lids.

Some worry acetaminophen may cause cancer

There's growing concern that your trusty bottle of Tylenol or generic acetaminophen might actually be a carcinogen. In 2016, Dr. Noel S. Weiss published a paper in the journal Cancer Causes & Control that reviewed a number of previous studies examining a connection between acetaminophen and various types of cancer. While no association was found between acetaminophen (even when taken in high doses or for long periods of time) and most types of cancer, some studies suggested that acetaminophen could increase risk for renal cell carcinoma, a type of kidney cancer.

Additionally, a few small studies found that lymphoma and leukemia risk were "modestly higher" among people who took acetaminophen. Weiss cautioned, however, that there are many limitations to these studies, including misidentification of acetaminophen users versus nonusers and a relatively short follow-up period, so further investigation is needed.

Although a possible link between acetaminophen and cancer is still uncertain, California lawmakers are, as of this writing, considering labeling the ingredient a carcinogen under Proposition 65, passed in 1986. The law requires warning labels for products that are known to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity. There are currently more than 900 substances on the list.