Strange Diet Trends From The Past You May Not Remember

For centuries, diet trends have been enticing people around the globe. Dieters have tried plenty of strategies in an attempt to stay or become lean, vigorous, and youthful. Americans spent more than $72 billion on dieting in one form or another in 2018 alone, MarketResearch.com revealed. Prescription obesity drugs took up a $655 million chunk of that pie. Diet books are also omnipresent, with more than 5 million sold on average each year, according to Nielsen BookScan (via Vox). Think of that: Millions of dieters spend billions of dollars each year in a never-ending quest to lose weight. And it's something that's been going on in our society for centuries.

No wonder, then, that humans have also dreamed up some of the wackiest, out there, so-unusual-they-just-might-work strategies for dropping pounds and losing inches. Walk back through time with us and take a peek at some of the strangest diets in weight-loss history — some of which you may even remember.

Lord Byron's vinegar diet

Move over Oprah Winfrey and Kim Kardashian. The world's first celebrity diet spokesperson, George Gordon Byron (more commonly known as Lord Byron), was a poet. Considered one of the top poets in British history, Lord Byron was an influential leader in early 19th-century London. He was also prone to extreme weight gain. To help keep his unwanted pounds under control, Byron adopted a diet of extremes, subsisting entirely on crackers, soda water, and potatoes drenched in vinegar for several days at a time, followed by large binge meals, reported BBC News.

Byron also chugged large quantities of apple cider vinegar in an effort to help suppress his hunger, according to Vice. Between the years of 1806 and 1811, this diet led Lord Byron to drop more than 70 pounds — something he wrote about extensively at the time.

With his immense fame and cultural reach, many of his followers adopted the diet as well in an attempt to replicate its effects. As such, Lord Byron became one of the first diet influencers; he "helped kick off the public's obsession with how celebrities lose weight," historian Louise Foxcroft told BBC.

The Graham Diet

Graham crackers, the happy-go-lucky s'mores building blocks, have a much darker origin story than you could've probably imagined. Created by minister and renowned vegetarian Sylvester Graham, graham crackers were originally the cornerstone of a diet craze designed to rid America of sexual deviancy. According to The Atlantic, Graham believed America was overrun with "sex, gluttony, and materialism." He also believed this gluttony was fueled by our overwhelming desire for the taste of meat, fat, and sugar.

Before long, thousands began following the Graham Diet, which "consisted of simply-prepared bland foods with lots of whole grains, mostly fruits and vegetables, and no spices, meat, alcohol or tobacco." It also called for small portions and only two meals per day. As his diet grew in popularity, Graham spoke out against a variety of ills he saw in the world: lack of exercise, masturbation, poor hygiene, and especially the evils of white flour (which he believed "did not give the teeth or the stomach a proper workout and it led to a lazy colon"). Enter the Graham cracker, which was originally created using an unrefined flour that Graham developed.

However, the crackers we know today weren't created until decades after his death when Nabisco added sugar to the recipe and started baking them en mass, which may just have Graham turning in his grave.

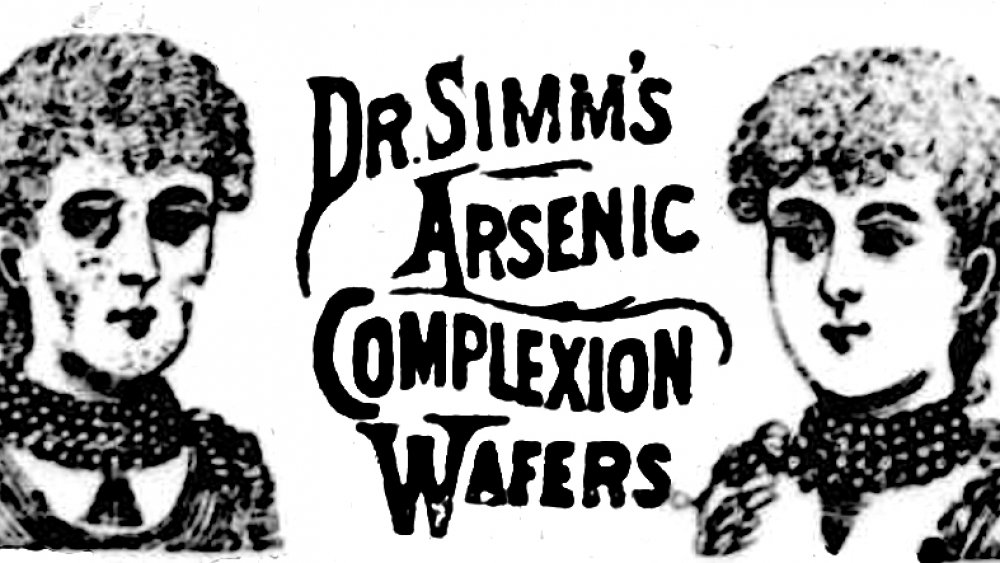

The arsenic supplement trend

As diet pills, supplements, and weight-loss potions grew in popularity during the late 19th century, researchers turned their efforts to Styria, located in southern Austria, where men and women consumed something called "ratsbane" with their daily coffee. What researchers may have considered a magical supplement was actually a form of arsenic.

According to Gizmodo, these early scientists deemed ratsbane safe and brought the arsenic habit back home, where they developed and began production of numerous wafers and other supplements containing arsenic — plus strychnine! What were they thinking? Well, in small doses, arsenic is a stimulant. A tiny dose, in theory, could spike a person's metabolism, physician and historian Michael Mosley told BBC's HistoryExtra. People also consumed ratsbane to "clarify their complexions and help them breathe more easily," according to Gizmodo.

Folks in Styria may have gradually built up a tolerance to arsenic, but the same was not true for English and American men and women who began consuming arsenic. Instead of dropping pounds, they started dropping dead at alarming rates. Obviously, that's not exactly ideal for the success of a growing health supplement business. By the '20s, arsenic was, thankfully, out of fashion.

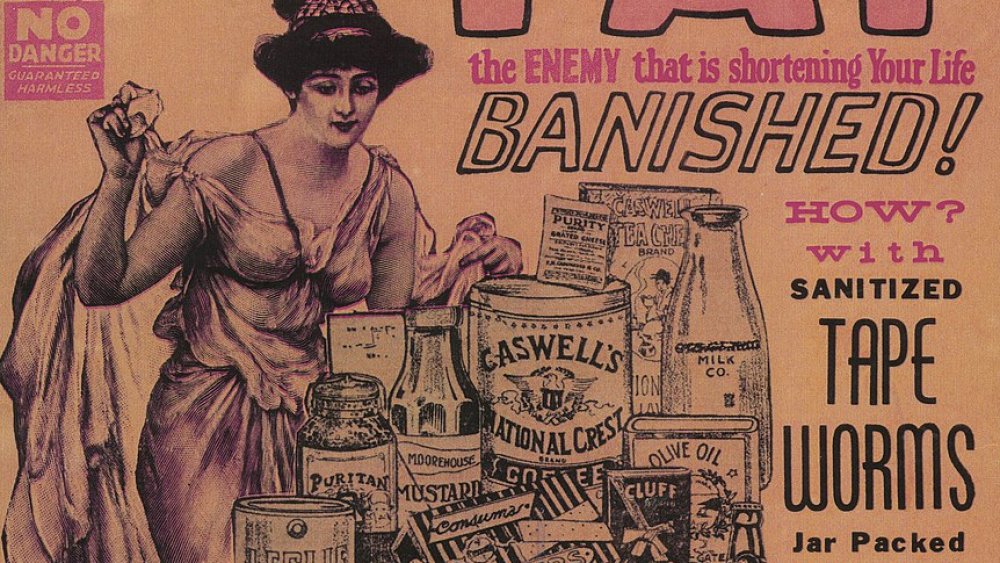

The tapeworm diet

The beauty trends of the Victorian era (1830s-1900) were driven by a bizarre notion of what was considered aesthetically pleasing: tuberculosis patients. Individuals with the illness, then called consumption, were pale with dilated eyes, pink cheeks, red lips, and an impossibly thin waist. Super-cinched corsets helped healthy women recreate the look, but they also achieved it an even more horrifying way: pills filled with tapeworm eggs.

Once in the stomach, the tapeworms would hatch and grow, reported Slate. As they matured, the worms consumed a portion of everything their host ate, allowing individuals to down full meals and still lose weight because of their body's reduced calorie intake. Once a weight loss goal was reached, different pills promised to rid the body of the tapeworm — or you could try a variety or truly horrifying home remedies designed to lure the tapeworm out of the body through, um, the opposite orifice from which it originally entered.

While some historians scoff at the idea and believe the pills that were distributed back then must've simply been placebos, MedicineNet warned the diet is still around and in active use in certain parts of the world. In the U.S., however, this is illegal.

Horace Fletcher's chewing diet

British tycoon Horace Fletcher, aka "The Great Masticator," reinvented what it meant to chew your food. The equivalent of an early 20th-century influencer, Fletcher was known for the diet trends he espoused. One of his favorites was the subject of his book, Fletcherism: What It Is, or, How I Became Young at Sixty. Fletcher believed in chewing every bite of food until it was more or less liquified.

"While the taste of a mouthful of food lasts, a necessary process is going on," American magazine explained in a 1906 review of the diet. "Liquid and solid should therefore be tasted and chewed until all taste has disappeared." Strange, yes, but Fletcher's diet appeared sound at the time. Tests conducted at Yale in the early 1900s showed Fletcher thrived on the plan and successfully completed the workouts of the school's crew team with "no evidence of soreness or lameness or distress of any kind."

However, in a 1919 story about his death, Time dissed the value of his diet, proclaiming that any weight lost while following it was likely just the result of people's mouths being tired (via NPR).

Cigarettes for weight loss

Cigarette companies have tried a lot of tricks to promote smoking over the years — from cartoon mascots to product placements to even physician testimonials. But one of the most underhanded and deceptive attempts to get more people smoking occurred in the early 20th century when a number of tobacco brands claimed that smoking could help men and, especially, women to lose unwanted pounds. It was one of the first times smoking advertisements had been directly aimed at female consumers, the anti-tobacco group Truth Initiative explained.

"Smoking had to be repositioned as not only respectable but sociable, fashionable, stylish, and feminine" the journal Tobacco Control revealed. Lucky Strike, for example, released two campaigns in 1928 and 1929 that were "designed to prey on female insecurities about weight and diet," Stanford University explained.

Just how effective was big tobacco's efforts? According to the CDC, as more and more weight-conscious, female-targeting ads were produced, the number of women between 18 and 21 "who began smoking tripled between 1911 and 1925 and had more than tripled again by 1939."

The grapefruit diet

Present in some form or another for about a century, the grapefruit diet is one fad that just won't quit. The first iteration of the program — called the "18-day diet" — featured varying combinations of grapefruit, oranges, toast, eggs, and vegetables. When added together, these foods totaled a remarkably skimpy 500 calories. The diet is thought to have originated in Hollywood in the 1920s and, eventually, it became a huge trend across the country, according to Hollywood and the Rise of Physical Culture.

The grapefruit diet has been reinvented over the decades, but grapefruit remains the main component. "Dieters eat grapefruit, drink grapefruit juice, or swallow grapefruit capsules at or before every meal," Health explained. Grapefruit's supposed superpower is a special enzyme that "burns" fat. This idea has been disproven, but researchers at Scripps Clinic did find that people who ate half a grapefruit or drank a glass of grapefruit before meals lost three pounds over 12 weeks without making any other changes to their diet. Yet and still, the most likely reason people lose weight on any version of the grapefruit diet is not due to grapefruit, but to cutting calories, reported WebMD.

The banana and milk diet

Bananas are packed with potassium, Vitamins C and B6, and high-quality fiber whereas milk is loaded with protein, calcium, and vitamin D. Individually, they're two incredible foods. But pair them together as the sole ingredients of a diet and you've got yourself a surefire load of weight-loss quackery. The banana and milk diet was likely invented in the early 1930s by physician George A. Harrop Jr. as a means of preventing diabetes, according to the Milwaukee Journal (via Livestrong). The diet called for eating four bananas each day, plus a few glasses of nonfat milk to wash them down. And that's it!

In addition to fighting disease, Dr. Harrop claimed the diet could trigger a drop of 6 to 10 pounds over two weeks' time, Livestrong reported. "For the patient who is willing to make reasonable sacrifices, the advantages of a simple, easily measured diet are quite obvious," Harrop explained in a 1934 article.

While such a low-calorie diet (less than 1,000 calories a day if followed to a tee) would almost certainly guarantee weight loss, research from the journal Healthcare warned that incredibly restrictive diets — you know, like the banana and milk diet — are inherently destined to fail. No shock there, of course.

The Drinking Man's Diet

Before South Beach or Atkins or the keto diet, there was The Drinking Man's Diet — a high-protein, low-carb meal plan with one distinct (and arguably highly enjoyable) difference over all the others that came after it. People who followed this plan were allowed to drink all the alcohol they desired with nary a hint of guilt.

Created by Robert Cameron, a San Francisco cosmetics executive, in 1964, The Drinking Man's Diet was a 60-page self-published book that retailed for just a buck, according to Forbes. Once released, sales soared past two million copies in less than a year.

Alcohol does have calories, of course, but Cameron reasoned that they weren't "bad" calories, NYU professor of nutrition Susan Yager explained to Today, of the "wildly popular" diet. Even more enticing, Forbes wrote was Cameron's promise of what else you could eat with impunity. "Most of the things you like best don't have to be counted at all: steak and whisky, chicken and gin, ham, caviar, pâté de foie gras, veal cutlets and vodka, frogs legs and lobster claws — they all count as zero," the book declared. Well, sign us up!

The Last Chance Diet

A number of fad diets over the years have been built around specially formulated foods or supplements you have to buy in order to bring about your weight loss. But unlike SlimFast, one unusual fad diet got its special secret ingredients from the hooves, bones, tendons, and animal hides left over at the local meat processing plant. Ladies and gentlemen, meet "The Last Chance Diet."

Created by physician Robert Linn in 1977, The Last Chance Diet encouraged followers to consume "a liquid protein supplement until they have lost their desired weight," The New York Times wrote at the time. A number of shakes with catchy names like Prolinn, GroLean, and Super Pro‐Gest became available to purchase but all were costly and said to taste terrible.

Still, the diet was popular, with more than two million followers, BBC reported. Since the protein shakes were incredibly low cal — just 300 to 400 calories per serving with barely any other nutrients outside of protein — weight loss was virtually guaranteed. However, nearly 60 individuals who had been following the diet experienced heart attacks. Before long, the diet's popularity rightfully waned (via AskMen).

The raw food diet

Man has been eating raw foods since the dawn of time. But U.S. News & World Report attributed the rise of the raw food movement to physician Maximilian Bircher-Benner who, in the late 1800s, found he could cure some of his ills by eating raw apples. The New York Academy of Medicine cites 1904 as a big year for the movement, as the authors of the book Uncooked Foods and How to Use Them boasted that they were able to regain perfect health after adopting a raw food diet for a year.

People's passion for raw food — especially sprouts, seeds, and juices — became popular once again in 1984 with the release of Leslie Kenton's book, Raw Energy: Eat Your Way to Radiant Health, which promoted a diet containing more than 75 percent raw foods.

In a review of the book, Publisher's Weekly wrote that the diet claimed to "reverse the effects of illness on the body, slow the aging process, increase energy levels, and improve emotional and mental health." The magazine continued, "This is a sensible and useful book for the nutritionally minded, but the authors may be overly enthusiastic in their cure-all claims."

The Fen-Phen trend

Fen-Phen, a drug combination of fenfluramine (appetite depressant) and phentermine (amphetamine), is the epitome of modern science's search for a miracle weight-loss pill — and the resulting downfall of that search. According to The New York Times, the Fen-Phen story begins in 1979 when Michael Weintraub, a pharmacologist at the University of Rochester decided to pair the two medications and see if they worked better together than they did on their own. To test the combo, he enrolled 121 test subjects in a trial. Soon, he found that individuals taking the medications had lower levels of hunger than participants taking a placebo. With that single study, a pharmaceutical empire was born.

European drug makers introduced a medication called Redux, which combined the two medications in one capsule. And in less than three months, doctors were writing 85,000 prescriptions for the pills each week, reported Time (via PBS's Frontline). The problem? Nobody had accurately tracked side effects of the medication. And they were serious, including heart disease, damage to valves in the heart, and even death.

By 1999, thousands of lawsuits against the drug manufacturer had been filed with proposed settlements topping almost $5 billion, the Los Angeles Times reported. And that was the end for Fen-Phen.

The Subway diet

It might seem strange looking back at it now, but for a time in the 1990s, the Subway diet seemed remarkable. Created and originally popularized by since-disgraced spokesperson Jared Fogle, a 6'2", 425-pound business major from Indiana University who lost a remarkable 225 pounds following the diet, the New York Daily News recapped. The diet called for eating a 6-inch turkey sub for lunch and a full-length veggie sub for dinner. A side of baked chips and a diet soda to wash it all down were okay, but hold the mayo, oil, and cheese to keep excess calories to a minimum.

Two weeks after the first Subway diet ad aired, Fogle was on Oprah telling America his story. According to Business Insider, sales at the fast food chain more than tripled as a result, with Fogle building what was once estimated at a $15 million net worth. These days, things are a little less rosy for the sandwich shop; the Subway diet is no longer trendy and the former spokesman is serving a lengthy prison sentence.

The Master Cleanse

The Master Cleanse is kind of like Jason Voorhees in the Halloween film franchise. It's popular for a while, goes into hiding, then stages a comeback. According to research from Cornell University, the original Master Cleanse started floating around in the 1940s. It then disappeared, only to reemerge in the 1976 best-seller aptly titled The Master Cleanser. It left the diet scene once more, only to be resurrected once more in 2007 when Beyoncé revealed she'd used it to drop 20 pounds in two weeks for her award-winning role in Dreamgirls.

Per The Master Cleanse website, the diet itself is a detox-style cleanse in which you're supposed to drink a mixture of lemon juice, cayenne pepper, and maple syrup for 10 days, followed by a nightly salt-water enema or laxative tea to help remove toxins from your body. But does it work?

The experts at WebMD doubt the effectiveness of the Master Cleanse and detoxing, in general. "Because you're getting so few calories, you'll probably lose weight," the site reported. However, the lack of nutrients will also eat away at your muscles and bones. Plus, WebMD cautioned, once you start eating normal again, "you're likely to gain the weight right back." Beyoncé even told Elle she'd "never" do the cleanse again.