A Complete Guide To Gluten And Your Health

As described in a 2018 study published in the journal Food Science and Technology Research, gluten is an umbrella term given to a composite of the two primary proteins in wheat: gliadin and glutenin. While gliadin accounts for the thick and gluey texture of wheat dough, glutenin imparts strength and elasticity to dough. Technically, gluten is not actually formed until wheat flour is mixed with water to make dough, according to a 2019 review of studies in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition. Rye and barley are also considered gluten grains because their main proteins are structurally related to the wheat protein gliadin.

Gluten is a ubiquitous ingredient and additive in the Western diet, notes a review article in a 2017 edition of the Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. However, certain fragments of the gliadin protein are not completely broken down through digestion in the gut. These undigested gluten fragments can stimulate adverse immune responses in people with celiac disease — an autoimmune disease that damages the small intestine and causes gut symptoms such as bloating and diarrhea. Increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut") induced by gluten may contribute to this heightened immune response (via Healthline).

Though less common than celiac autoimmune reactions, gluten proteins in wheat can also elicit an allergic reaction in some individuals that causes swelling, hives, asthma, and other classic allergy symptoms, continues the 2017 article. Some people without celiac disease or wheat allergy may nevertheless experience similar gut symptoms (as those with celiac disease) when consuming gluten. These individuals have non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and respond well to a gluten-free diet. A gluten-free diet for life is the established treatment for celiac disease.

Foods containing gluten

Gluten is primarily found in foods containing wheat, barley, or rye (via the Mayo Clinic). Triticale is a hybrid of wheat and rye and thus contains gluten as well. Gluten is also found in varieties of wheat including spelt, kamut, einkorn, emmer, and durum. Flours made from gluten-containing wheat also come with different names (e.g., enriched flour, graham flour, farina, self-rising flour, and semolina. The case of oats and gluten is a bit tricky, according to Healthline. Though the protein in oats, avenin, is structurally related to the gluten proteins, it is substantially less capable of activating an immune response. Though rare, a small percentage of people with celiac disease may still react to oats. Nevertheless, in the vast majority of celiac cases, oats are well tolerated, provided they are certified and labeled gluten-free (due to possible contamination from other gluten grains).

Among the multitude of processed grain products that contain gluten, continues the Mayo Clinic, are breads, crackers, pasta, cookies, croutons, bulgur wheat, cakes, pies, matzo, and communion wafers. In addition to being a constituent of grain-based foods, wheat gluten is used in many processed foods as a thickener, stabilizing agent, flavoring, or coloring. Included among these processed foods and beverages are beer, ale, porter, stout, candies, French fries, gravies, imitation meat or seafood, malt, hot dogs, lunchmeats, salad dressings, sauces (e.g., soy sauce), potato and tortilla chips, self-basting poultry, soups, and bouillon cubes. Gluten may also be used as a binding agent in some medications and dietary supplements. Supplement manufacturers are required to indicate "wheat" on the product label if the supplement contains wheat gluten.

History of gluten in bread making

Over the past 2,000 to 5,000 years, farmers may have indirectly selected for a substance (later identified as gluten) in wheat to improve dough quality for bread making, according to a review of studies published in a 2019 edition of the journal Nutrients. Thus, for technological reasons, the amount of gluten in wheat has been increasing over the many centuries since humans started making bread.

A difference in the composition of gluten — or an increase in the gluten content of modern grains — has been suggested to play a part in the increasing prevalence of celiac disease in the past 50 to 70 years. Of the two gluten proteins, gliadin carries the toxic fragments that trigger undesirable immune reactions. Ancient grains that date back thousands of years ago contain a more digestible gluten that has considerably fewer toxic fragments.

However, according to Science News, the gluten content of wheat has not changed over the past 120 years, the latter part of which is associated with a marked increase in the occurrence of celiac disease. In fact, there has been a slight decrease in the number of toxic gliadin fragments during this period. While these findings do not support increased gluten content of modern wheat as a cause of the rising rates of celiac disease, increased consumption of wheat flour and greater use of gluten as a food additive are more likely to be contributing factors, according to a 2013 study published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

Digestion of gluten

After partial digestion in the stomach, dietary proteins pass into the small intestine where they are broken down into free amino acids by pancreatic enzymes, as described by a 2020 study published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. The amino acids are then absorbed by the small intestine and released into the bloodstream. However, gluten proteins in wheat, rye, and barley are poorly digested. The component proteins of gluten have a peculiar composition that is characterized by high concentrations of two amino acid "building-blocks," proline and glutamine, that render part of the gluten protein resistant to compete degradation by digestive enzymes (via a 2021 review of studies in the journal Pharmaceutics). In wheat gluten, the gliadin fraction is especially rich in these amino acids, while secalin and hordein are the gluten-like counterparts in rye and barley respectively. While normally harmless, in predisposed people these undegraded protein fragments (peptides) are toxic — they trigger an immune response that leads to intestinal damage and celiac disease.

New findings from the 2020 study indicate that the capacity to completely degrade gluten is present from birth. However, the ability to digest gluten wanes after six months. By the age of 12 months, the toxic peptides from gluten digestion can no longer be degraded. Interestingly, it is suggested that the capacity to effectively break down gluten may be impacted by changes in the infant intestinal microbiota. The intestinal microbiota produces digestive enzymes that can further degrade gluten. The maternal and/or infant diet, exposure to antibiotics, and the surrounding environment may play a major role in the bacterial colonization of the infant gut.

Gluten and leaky gut

A single layer of epithelial cells lining the gastrointestinal tract partitions the inside of the body from the outside environment, notes a review article published in a 2019 edition of the journal Nutrients. This gut barrier includes "tight junctions" between the epithelial cells that regulate the flow of molecules in and out of the GI tract. Normally, nutrients are allowed in while harmful pathogens and environmental toxins are kept out. When intestinal barrier function is compromised, however, intestinal permeability — or "leaky gut" — is increased. In several autoimmune conditions — including celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, and multiple sclerosis — increased intestinal permeability plays a role in the development of the disease (via a 2020 review of studies published in F1000Research).

According to a 2016 review published in the journal Tissue Barriers, one established mechanism of increased intestinal permeability is the secretion in the gut of abnormally high levels of a protein called zonulin, which plays a prominent role in "tight junction" control. When too much zonulin is secreted, these junctions are weakened and the intercellular (between cells) spaces open up to a greater extent, allowing passage of large molecules, including gluten, into the bloodstream. Gluten itself is a potent trigger of zonulin release into the gut, even in healthy people. However, whereas zonulin secretion is minimal and transient in healthy individuals, zonulin is released in much higher concentrations and for a prolonged period following consumption of gluten in people with celiac disease. This leads to leaky gut and exposure to toxic gluten fragments that provoke an autoimmune attack.

Gluten and autoimmune disease

As explained by a 2020 review of studies published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, a new model for autoimmune disease has emerged. In this new model, the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease consists of three main features: a genetic predisposition, increased intestinal permeability ("leaky gut"), and an environmental trigger. Gluten has been identified as the environmental trigger responsible for autoimmunity in celiac disease, reports a review of studies published in a 2020 edition of the journal Nutrients. Some evidence suggest that gluten may also play a role in several other autoimmune disorders (e.g., psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, and autoimmune thyroid diseases). All of these autoimmune conditions are known to be associated with celiac disease — they often coexist. In fact, having one autoimmune disease significantly raises the risk of developing others (via MedlinePlus).

Human and animal studies have shown a particularly strong connection between gluten and type 1 diabetes, continues the 2020 review. For example, adherence to a gluten-free diet over the first year following type 1 diabetes diagnosis in non-celiac children was associated with better blood sugar control and a prolonged partial remission period. Approximately 6% of people with type 1 diabetes also have celiac disease (per Celiac Disease Foundation).

Gluten and celiac disease

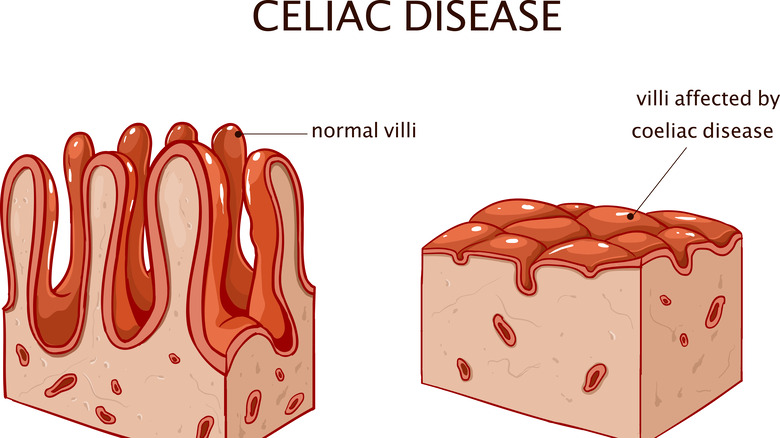

Celiac disease is a lifelong inflammatory and autoimmune disorder that occurs in about one in 100 people globally, reports the NIH. In people genetically predisposed, gluten from wheat (as well as rye and barley) triggers a destructive immune response. The immune system recognizes incompletely digested gluten as a "foreign" substance and proceeds to mount an attack against it, causing "collateral" damage and inflammation to the lining of the small intestine. While diarrhea, weight loss, and recurrent bloating and abdominal pain affect 40%50% of people with celiac disease, most people experience mild or no symptoms. Flattening of the intestinal villi (fingerlike projections where nutrient absorption occurs) can cause nutrient malabsorption, resulting in deficiencies of iron and vitamins B12, D, and K (via Medical News Today).

The treatment for celiac disease is strict, lifelong compliance with a gluten-free diet, which significantly improves symptoms within days or weeks. This means avoiding all foods containing wheat, rye, barley, and their derivatives, as well as gluten-containing non-foods such as medicines and supplements. As required by the FDA, food products can only be labeled gluten-free if they contain less than 20 parts per million of gluten. Untreated celiac disease can lead to the development of osteoporosis, infertility or recurrent abortion, neurologic disorders, and, in rare cases, cancer (per the NIH).

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity

People without celiac disease or wheat allergy can experience symptoms in response to gluten ingestion and improvement in symptoms when gluten is removed from the diet, explains the Cleveland Clinic. These symptoms resemble those associated with celiac disease and include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and other intestinal symptoms, as well as non-intestinal symptoms such as depression, headache, and joint pain. This gluten intolerance syndrome is known as non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and is much more common than celiac disease, with an estimated prevalence of 6% of the U.S. population.

Since there are no specific diagnostic tests or biomarkers for NCGS, a diagnosis can be made by ruling out wheat allergy and celiac disease (via the NIH). Gluten may not be the only cause of NCGS symptoms. GI symptoms of NCGS overlap with symptoms (e.g., gas, bloating, diarrhea) caused by consumption of a group of carbohydrate foods known as FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols).

Since FODMAPs are found in gluten grains, it has been suggested that these carbohydrates, rather than gluten (or in addition to gluten) contribute to the symptoms of NCGS. A low FODMAP diet has been shown to improve GI symptoms in people with non-celiac gluten sensitivity, according to a 2022 review of studies published in the British Journal of Nutrition.

Gluten and Hashimoto's thyroiditis

Hashimoto's thyroiditis is an autoimmune disorder in which thyroid antibodies attack and destroy thyroid tissue, explains Healthline. The presence of these antibodies (thyroid peroxidase antibodies and thyroglobulin antibodies) is detected in the blood of people with Hashimoto's disease. Hashimoto's is a common cause of hypothyroidism (low thyroid) and the associated symptoms of fatigue, dry skin, hair loss, constipation, and weight gain. These symptoms coincide with high levels of thyroid antibodies.

Hashimoto's disease and other thyroid disorders may be impacted by gluten ingestion (via Heathline). This may be due to cross-reactivity of the immune system whereby thyroid antibodies cannot distinguish between the structurally similar gluten peptides (gliadin) and thyroid proteins. Consequently, gluten consumption in people with Hashimoto's can trigger an immune attack. Some evidence suggests that a gluten-free diet may clinically benefit people with Hashimoto's. In a pilot study published in a 2019 edition of Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, a gluten-free diet resulted in reduced levels of thyroid antibodies and increased secretion of thyroid hormones in women with Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Gluten and the health of the brain and nervous system

Apart from the typical gastrointestinal symptoms, people with celiac disease may also experience extraintestinal (outside the gut) symptoms that include adverse effects on the health of the brain and nervous system (via a 2020 review of studies published in the journal OBM Neurobiology). Gluten ingestion in celiac patients may result in brain atrophy as well as neurological disorders such as peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, migraines, and ataxia (lack of muscle coordination). While mild cognitive impairment is common in adults with celiac disease, some adults may develop Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia, notes a 2018 review published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Strong evidence suggests that anti-gluten antibodies damage the brain through "proinflammatory" or "cross-reactivity" mechanisms. One mechanism for gluten's effects on the brain is a cross-reaction between antigluten antibodies and a protein found in nerve cells called synapsin I. Due to the similar chemical structure shared by gluten and synapsin 1, the immune system mistakenly attacks and inflames nerve tissue.

Another mechanism involves tissue transglutaminase (tTG) — an enzyme that is attacked by antibodies in people with celiac disease (via a study published in a 2013 edition of Schizophrenia Bulletin). A positive blood test for tTG is suggestive of celiac disease. A structurally similar form of tissue transglutaminase called transglutaminase 6 (tTG6) is found primarily in the brain and nervous system. The presence in the blood of antibodies against this enzyme is a marker of gluten ataxia and neuroinflammation. This suggests that tTG6 triggers a gluten-related autoimmune attack leading to neuroinflammation, just as tissue transglutaminase provokes autoimmune-directed intestinal inflammation.

The gluten-free diet

A gluten-free diet for life is mandatory in the management of gluten-related disorders such as celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, wheat allergy, and gluten ataxia, reports the Mayo Clinic. Even some people without gluten intolerance are avoiding gluten because of the claims that going gluten-free may improve overall health, weight loss, gut health, energy levels, and athletic performance. Foods and beverages to avoid on the diet include any product made with wheat, rye, barley, triticale, or oats (unless labeled "gluten-free oats"). A myriad of processed foods, medications, and supplements may also contain gluten as an additive; thus, reading labels is important.

According to the Celiac Disease Foundation, focusing on foods that are naturally free of gluten is a sensible and healthy way to comply with the diet. Naturally gluten-free foods include fruits, vegetables, meat and poultry, fish and seafood, dairy, beans, legumes, and nuts. Among the non-gluten grains are amaranth, arrowroot, buckwheat groats, corn, millet, quinoa, sorghum, teff, and rice. Some starchy foods (e.g., tapioca, potato, cassava) and various nuts can be used to make gluten-free flours. A multitude of gluten-free alternatives are available in grocery stores to make the diet easier to follow. When reading food labels, it's important to know that just because something is "wheat-free" doesn't mean it's "gluten-free."

Should everyone avoid gluten?

Staying clear of gluten is critical for people with gluten-related disorders and logical for those who feel worse after eating gluten, notes Harvard Medical School. As for everyone else, claims of health benefits from gluten restriction are not supported by strong evidence. Nevertheless, avoiding gluten continues to be popular for a variety of reasons. For example, it is believed that the inflammatory and overall negative effects of gluten in celiac disease could also occur in healthy people. Also, testimonials about how gut symptoms vanished while eating gluten-free can be pretty convincing for some individuals. Moreover, celebrity endorsements and clever marketing of gluten-free products and related books can be influential as well.

Importantly, there are some downsides to the complete elimination of gluten in the diet, explains a 2017 article published in the journal Diabetes Spectrum. For example, gluten-free foods are considerably more costly than conventional foods. Gluten-free bread and bakery products have been found to be, on average, 267% more expensive than traditional breads. There are also nutritional concerns associated with gluten avoidance. Processed gluten-free products are frequently lacking in fiber, zinc, potassium, and trace minerals. Foods that are not fortified may be low in iron and B vitamins as well.